A Woman With Seventh Nerve Palsy: Presentation and Management

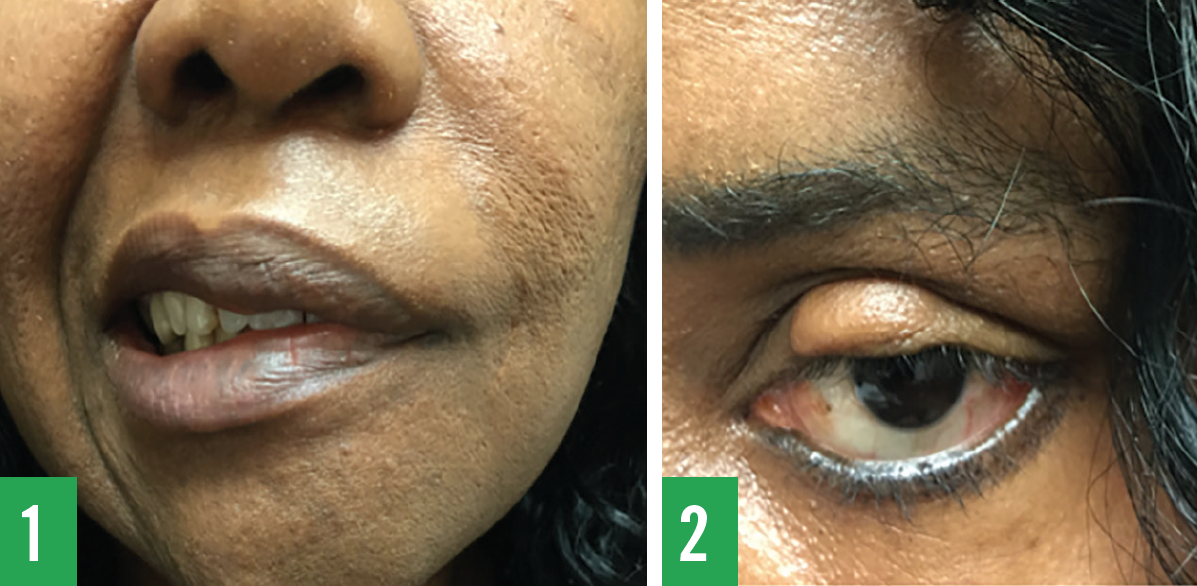

A 48-year-old woman presented with left-sided facial paralysis. She stated that the facial weakness (Figure 1) with accompanying mild left ear pain had started approximately 4 years ago. Since then, she had experienced uncomfortable hearing in her left ear, particularly in crowded and noisy places, and her taste sensation had not been the same as before. She was unable to close her left eye (Figure 2) while trying to sleep and used a pillow to keep it covered. The lagophthalmos and consequent corneal exposure had resulted in severe dry eyes and discomfort.

Her past medical history included hypertension and obesity. She denied a history of dizziness, facial trauma, and recent flulike illness. She was unemployed, and her personal and family histories were noncontributory.

Physical examination findings included the following values: temperature, 36.5°C; pulse, 88 beats/min; blood pressure, 122/78 mm Hg; height, 170 cm; weight, 86.2 kg; and body mass index, 29.8 kg/m2. She had left-sided facial drooping with evidence of being unable to close her upper eyelid and mouth, wrinkling of the left side of the forehead, and aching of the left ear with sensitivity to sound. Both tympanic membranes appeared normal. Motor activity of the left forehead had a blunted appearance, including a blunted left nasolabial fold.

Based on these findings, the woman received a diagnosis of Bell palsy.

Discussion

Bell palsy is one of the most common forms of facial paralysis affecting the seventh cranial nerve (facial nerve). Weakness of the seventh cranial nerve may begin with symptoms of pain in the mastoid region, affecting normal hearing and producing full or partial paralysis of one side of the face.1,2 Facial paralysis results from interruption at any level of the seventh cranial nerve; the paralysis can be complete or partial and can result in decreased salivation, tearing disorders, hyperacusis, and hypoesthesia of the external auditory canal.3

Patients with Bell palsy also commonly experience an upper eyelid that cannot be closed and a drooping lower eyelid. The eyelids stay open even as the person sleeps, resulting in prolonged dryness that can lead to corneal ulcers, infection, perforation, and loss of vision. Implantable devices have been used to restore dynamic lid closure in cases of severe, symptomatic lagophthalmos.4,5

The seventh cranial nerve has motor functions and sensory functions. The motor function allows for facial expression and secretion of saliva and tears, while the sensory function allows for taste and muscle proprioception. The seventh cranial nerve originates in the pons and is located lateral and anterior to the abducens nucleus. The nerve enters the internal auditory meatus with the eighth cranial nerve (vestibulocochlear nerve), then forms the geniculate ganglion, where it bends into the facial canal and exits the skull through stylomastoid foramen. The nerve finally passes the parotid gland and subdivides into the temporal, zygomatic, buccal, marginal mandibular, and cervical branches, enervating the corresponding facial muscles.

Damage to the seventh cranial nerve at the stylomastoid foramen results in paralysis of all facial muscles. In addition, the patient will experience an absence of facial creases and skin folds (especially on the forehead), a decrease in taste sensation, drooping of the lower eyelid, and a depressed angle of the mouth.

During the physical examination of the face, certain signs can help pinpoint the location of lesion of the seventh cranial nerve (Table). It is important to identify and document the location of the lesion to aid in assessment and the treatment plan.

The differential diagnosis of Bell palsy includes Ramsay Hunt syndrome, acoustic neuroma, and brainstem glioma. Ramsay Hunt syndrome is the result of the reactivation of varicella zoster in the geniculate ganglion, and it is characterized by facial palsy and an associated vesicular eruption in the pharynx and external auditory canal. The patient may present with associated symptoms such as tinnitus, hearing loss, nausea, vomiting, and vertigo.

Acoustic neuroma, a tumor on the eighth cranial nerve, may cause similar symptoms. Brainstem gliomas may cause similar effects over the seventh cranial nerve.

Management

The American Academy of Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery Foundation6 and the American Academy of Neurology7 both have recently published guidelines for the treatment of Bell palsy. Generally, the initial treatment of Bell palsy is glucocorticoids; prednisone, 60 mg daily for 5 days, then tapered to 10 mg for the next 5 days, for a total treatment of 10 days, can be given to shorten the recovery period and improve functional outcome. Reports have suggested a possible connection between Bell palsy, herpes simplex virus, and varicella zoster virus; therefore, antivirals such as acyclovir also could be prescribed. Nevertheless, recent reports have indicated that treatment of Bell Palsy with acyclovir alone or simultaneously with prednisolone does not show any advantage, and that prednisolone alone is as effective.8-10

Because the functions of the seventh cranial nerve are complex, a number of problems can arise from prolonged Bell palsy. The eye is one of the most sensitive and easily damaged organs by Bell palsy. The inability to close the eyelids may lead to dryness and corneal abrasion. Artificial tears should be applied every hour during the time the patient is awake.11 For additional eye protection, protective glasses should be prescribed. The degree of lagophthalmos and the necessity to use eye lubricants can be addressed with surgery (implanted upper eyelid weights or tarsorraphy).5

Our patient underwent implantation of pretarsal stainless steel weights in her left upper eyelid, which allowed her to close her eye, thus preventing potential corneal damage and allowing her to sleep comfortably (Figure 3).

Syed A. A. Rizvi, PhD, is a professor in the Department of Pharmaceutical Sciences, College of Pharmacy, at Nova Southeastern University in Fort Lauderdale, Florida, and is clinical research director at JAS Medical Management, LLC, in Miramar, Florida.

Rudy Lacosse, PA-C, is a physician assistant in Miramar, Florida.

Ayman M. Saleh, PhD, is a professor of biochemistry and molecular biology at the College of Applied Medical Sciences at King Saud bin Abdulaziz University for Health Sciences and a senior research scientist at King Abdullah International Medical Research Center, National Guard Health Affairs, both in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia.

April S. Brown, PharmD, is chief executive officer and president of PharmTec, Inc, in Fort Myers, Florida.

Jasmin Ahmed, MS, is a fourth-year medical student at the School of Medicine at Spartan Health Sciences University in Vieux Fort, St Lucia.

Sultan S. Ahmed, MD, is a clinical associate professor of medicine at Nova Southeastern University in Fort Lauderdale, Florida, and medical director of JAS Medical Management, LLC, in Miramar, Florida.

References:

- Adour KK. Current concepts in neurology: diagnosis and management of facial paralysis. N Engl J Med. 1982;307(6):348-351.

- Valença MM, Valença LP, Lima MC. Idiopathic facial paralysis (Bell’s palsy): a study of 180 patients [in Portuguese]. Arq Neuropsiquiatr. 2001;59(3-B):733-739.

- Ahmad SJ, Rather AH. A prospective study of physical therapy in facial nerve paralysis: experience at a multispeciality hospital of Kashmir. J Med Sci. 2012;15(2):145-148.

- Lee V, Currie Z, Collin JRO. Ophthalmic management of facial nerve palsy. Eye (Lond). 2004;18(12):1225-1234.

- Rahman I, Sadiq SA. Ophthalmic management of facial nerve palsy: a review. Surv Ophthalmol. 2007;52(2):121-144.

- Baugh RF, Basura GJ, Ishii LE, et al. Clinical practice guideline Bell’s palsy. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2013;149(3 suppl):S1-S27.

- Gronseth GS, Paduga R, American Academy of Neurology. Evidence-based guideline update: steroids and antivirals for Bell palsy: report of the Guideline Development Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology. Neurology. 2012;79(22):2209-2213.

- Sullivan FM, Swan IR, Donnan PT, et al. Early treatment with prednisolone or acyclovir in Bell’s palsy. N Engl J Med. 2007;357(16):1598-1607.

- Goudakos JK, Markou KD. Corticosteroids vs corticosteroids plus antiviral agents in the treatment of Bell palsy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2009;135(6):558-564.

- Sullivan FM, Swan IR, Donnan PT, et al. A randomised controlled trial of the use of aciclovir and/or prednisolone for the early treatment of Bell’s palsy: the BELLS study. Health Technol Assess. 2009;13(47):iii-iv, ix-xi 1-130.

- Holland NJ, Weiner GM. Recent developments in Bell’s palsy. BMJ. 2004;329(7465):553-557.