Why Does This Boy Have Multiple Joint Contractures?

AUTHORS:

Waleed Kurtom, MD; Andrew J. Degnan, MD; Katherine G. Langley, MS; and Samantha A. Schrier Vergano, MD

CITATION:

Kurtom W, Degnan AJ, Langley KG, Schrier Vergano SA. Why does this boy have multiple joint contractures? Consultant for Pediatricians. 2016;15(7):370-371.

An 8 year-old boy who recently emigrated from El Salvador was referred initially to a rheumatologist for concerns of arthrogryposis multiplex congenita, specifically with contractures of the distal interphalangeal joints. He was reported to also have cardiac anomalies. A recent echocardiogram revealed polyvalvular dysplasia, mitral valve stenosis and regurgitation, and a bicuspid aortic valve. After the rheumatologic evaluation, the diagnosis of arthrogyposis multiplex was questioned. The patient was referred to our genetics clinic where physical examination results were significant for hepatomegaly, corneal clouding, and gingival hypertrophy. Laboratory test results ultimately demonstrated elevated levels of urinary heparan and dermatan sulfate as well as significant reduction in the enzyme α-iduronidase.

Figure 1. Facial photo of the patient at 8 years of age. Note the coarse features, with broad nasal root, full cheeks, thick eyebrows, and wide mouth.

Figure 2. The patient’s right hand, demonstrating contractures at the distal and middle interphalangeal joints.

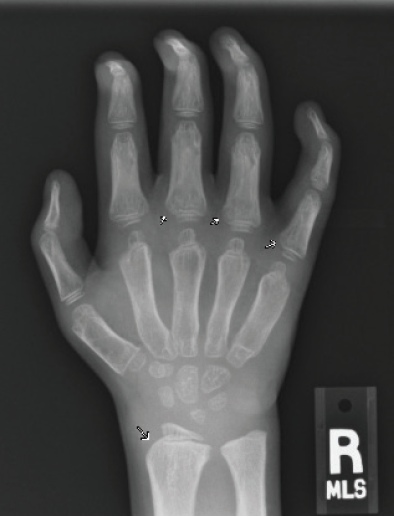

Figure 3A. Posteroanterior radiograph of the left hand.

Figure 3B. Posteroanterior radiograph of the right hand. Posteroanterior radiographs of both hands demonstrate fixed contractures of the distal interphalangeal joints, slightly “bullet-shaped” phalanges with osteopenia, broadening of the metacarpals, and dysplastic appearance of the distal radii.

What is causing this boy's symptoms?

(Answer and discussion on next page)

ANSWER: Hurler-Scheie syndrome/mucopolysaccharidosis type I

DISCUSSION

The results of laboratory testing and physical examination were consistent with a diagnosis of mucopolysaccharidosis Type 1 (Hurler/Hurler-Scheie syndrome, an autosomal recessive storage disorder caused by deficiency in the lysosomal enzyme α-L-iduronidase (IDUA), resulting in the accumulation of glycosaminoglycans in tissues throughout the body.1 Lysosomal storage disorders are rare but potentially life-threatening conditions with symptoms that may manifest in multiple organ systems or tissues. Although clinical presentations may vary, joint involvement is not unusual.

The disease incidence is approximately 1 in 100,000 newborns. Cardiac, respiratory, skeletal, ophthalmologic, and central nervous system function can be impaired. MPS I is subdivided into three main phenotypes: Hurler (early onset, rapidly progressive, with neurodegeneration), Scheie (later onset, less rapid progression, without neurodegeneration), and Hurler-Scheie (onset and progression between that of Hurler and Scheie, with mild or absent central nervous system involvement).2 Measurement of urinary glycosaminoglycan levels is commonly used as a screening test for MPS I but is fairly nonspecific and may produce false-negative results depending on urinary concentration. Definitive diagnosis of MPS I is made by enzyme assay demonstrating deficient IDUA activity in fibroblasts, leukocytes, serum, or dried blood spots, and can be confirmed by DNA analysis demonstrating mutation in both iduronidase alleles.3

Treatment. Once the diagnosis is established, enzyme replacement therapy with laronidase has been shown to treat many aspects of MPS I. Laronidase therapy has been effective in delaying disease progression in more severe phenotypic manifestations and has been beneficial in treating patients with delayed diagnosis. Without prompt diagnosis and treatment, approximately 75% of patients with severe MPS I die before age 10 years, usually from obstructive airway disease, respiratory infection, and cardiac complications.4

Early recognition. Early recognition of symptoms and subsequent diagnosis are essential to achieve optimal long-term prognosis in patients with MPS I. General pediatricians as well as specialists such as rheumatologists and cardiologists should be familiar with the clinical manifestations of this disease. Beck et al created a review of the natural history of MPS I using the MPS I registry.5 Their data revealed that hernias were the earliest presenting symptoms in all three phenotypes. In addition, coarse facial features and corneal clouding were also highly specific for MPS I across the phenotypes. In terms of musculoskeletal abnormalities, kyphosis/gibbus was the only abnormality present in the majority (70%) of patients with the Hurler phenotype.5 Joint contractures and carpal tunnel syndrome were present in the majority of Scheie patients (69.3 and 51.2%, respectively) but were less common in Hurler–Scheie patients (57.3 and 27.8%, respectively) and even less frequent in Hurler patients (37.9 and 7.8%, respectively).5

CASE DETAILS

Our patient had mitral valve prolapse with mitral regurgitation, scoliosis, and significant joint contractures of his fingers, hands, and lower extremities that had been initially diagnosed as arthogyroposis multiplex congenita. He also had 3 testicular surgeries and a repaired ventral hernia. His family history was not significant for any heritable heart disease, arrhythmias, sudden cardiac death, or connective tissue disorder. He was the seventh child of the nonconsanguineous union of his mother and father and had 6 older siblings, all of whom were healthy. There was little further family history available on both the maternal and paternal sides. Despite the autosomal recessive inheritance of Hurler-Scheie syndrome, physical examination results suggested the diagnosis.

Physical Examination. The boy’s corneas appeared to be “steamy” and his face was typical of mucopolysaccharide storage (Figure 1), with coarse facial features, a wide mouth, and broad nasal bridge. He also had gingival hyperplasia (Figure 1), and his hands demonstrated joint contractures mostly involving the fingers and elbows (Figure 2).

Figure 1. Facial photo of the patient at 8 years of age. Note the coarse features, with broad nasal root, full cheeks, thick eyebrows, and wide mouth.

Figure 2. The patient’s right hand, demonstrating contractures at the distal and middle interphalangeal joints.

A grade 2-3/6 mid-pitched regurgitant, late peaking systolic murmur was heard primarily at the apex and the left lower sternal border, and there was a grade 1/6 diastolic flow rumble. Abdominal examination results were significant for a periumbilical abdominal scar consistent with a hernia repair and a small residual ventral hernia. A 15-lead electrocardiogram demonstrated normal sinus rhythm; possible left ventricular hypertrophy, and nonspecific ST-T wave changes. An echocardiogram was completed and revealed polyvalvular dysplasia, especially of mitral valve and aortic valve. It also showed mitral valve thickening/dysplasia with mild prolapse and chordal abnormalities associated with moderate mitral regurgitation. Based on the initial history, physical examination results, and findings from the echocardiogram, the patient was referred to rheumatology and medical genetics.

History obtained by the rheumatologist indicated that for the last 2 years, the patient had experienced worsening pain of his knees and particularly his ankles, wrists, and lower back. He also had had progressive claw-hand deformities of both of his hands, though he did not have any significant swelling. The involvement of his hands and wrists had worsened to the point where it affected his ability to use his hands, particularly to put on his clothes.

His physical examination results were notable for limited extension of his cervical spine and some mild limitation to lateral movements. He exhibited limited flexion at his elbows, and his knees were grossly deformed. He also demonstrated mild flexion deformities at both hips. He had significant limitation of both wrists but no apparent soft tissue swelling, and he had flexion deformities involving all distal interphalangeal (DIP) joints of the fingers of both hands. He had marked limitation of flexion at his metacarpophalangeal (MCP) and proximal interphalangeal (PIP) joints, and he was unable to form a fist fully.

Laboratory and radiologic evaluations. Based on physical examination findings, the rheumatologist was concerned that the child may have a lysosomal storage disease. A urine specimen was collected and tested for glycosaminoglycan and oligosaccharide levels. In addition, radiographs of his neck, elbows, wrists, hips and back were obtained.

There were multiple abnormalities noted in several of these images. The hips and pelvis were noted to have bilateral coxa valga, and the lateral aspects of both femoral heads were incompletely covered by the acetabulae. His sacroiliac joints were noted to be widened, and the lumbar spine demonstrated shortened height of the vertebral bodies. There was soft tissue swelling or redundancy at the bilateral wrists and decreased bone mineralization. Images of his elbows showed loss of skin folds at the bilateral anterior elbows consistent with soft tissue swelling, possibly related to chronic contractures. Views of his hand showed moderate fixed flexion of the bilateral DIP joints along with bilateral soft tissue swelling, enlargement, osteopenia and gross abnormalities (Figures 3A and 3B). The lumbar spine images showed vertebral body height loss as well as posterior vertebral body scalloping most pronounced at the lower lumbar spine. It was also noted that on the anteroposterior view there was demonstration of possible hepatomegaly. Overall, interpretation by pediatric radiology noted that the findings raised concern for a possible underlying genetic disorder.

Figure 3A. Posteroanterior radiograph of the left hand.

Figure 3B. Posteroanterior radiograph of the right hand. Posteroanterior radiographs of both hands demonstrate fixed contractures of the distal interphalangeal joints, slightly “bullet-shaped” phalanges with osteopenia, broadening of the metacarpals, and dysplastic appearance of the distal radii.

Shortly thereafter, he was seen by medical genetics. Additional information obtained included that he was the product of a 41-week gestation complicated by advanced maternal age. His mother recalled that he had had measles when he was a few years old, and shortly after the illness his hands “curled” and his gums seemed to grow down between his teeth. His mother associated these changes directly with the history of measles.

Lysosomal enzyme analysis was sent, which confirmed reduction of the enzyme iduronidase and the diagnosis of MPS 1. The child’s cognitive development was normal, so he was felt to have an attenuated form of MPS 1, most consistent with Hurler-Scheie. Laronidase treatment was initiated, and the boy has made significant improvement in many realms, including mobility and range of motion at his joints.

CONCLUSION

Patients with lysosomal storage disorders can present to primary care providers as well as to subspecialists with varying symptoms and at different stages in their disease course. In this case, the patient presented to our care team with reported arthogryposis multiplex congenita and cardiac abnormalities. Arthogryposis multiplex congenita describes congenital joint contractures in 2 or more areas of the body and can be associated with cardiac abnormalities.6 Musculoskeletal manifestations of lysosomal storage disorders such as MPS I can share features with arthrogryposis multiplex congenital, including contractures and an abnormal radiocarpal angle. However, additional radiographic findings in mucopolysaccharidoses not seen with arthrogryposis multiplex congenita include components of dysostosis multiplex such as calvarial thickening, anterior beaking of the vertebral bodies causing kyphosis, bullet-shaped phalanges, proximal humeral erosions, small iliac bones, abnormal femoral head morphology, odontoid hypoplasia, scoliosis, and thickened tubular bones (eg, clavicles and ribs).7-9

This report emphasizes the importance of a thorough history and physical examination in situations where a previous diagnosis is assumed but not necessarily confirmed. Our patient was properly diagnosed after careful history and physical examination by a physician team including cardiology, rheumatology, and medical genetics. As a result, he received appropriate enzyme replacement therapy. Early pediatric recognition and referral of MPS disorders is essential because early initiation of enzyme replacement therapy can improve morbidity and mortality.10,11 Thus, familiarity with the key features of MPS I by pediatricians and subspecialists is crucial for improved patient outcomes.

Waleed Kurtom, MD, is a third-year pediatric resident at the Children’s Hospital of The King’s Daughters.

Andrew J. Degnan, MD, is a fourth-year radiology resident at the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center in Pennsylvania.

Katherine G. Langley, MS, is a genetic counselor in the Division of Medical Genetics and Metabolism at the Children’s Hospital of The King’s Daughters in Norfolk, Virginia.

Samantha A. Schrier Vergano, MD, is the Division Director of Medical Genetics and Metabolism at the Children’s’ Hospital of The King’s Daughters in Norfolk, Virginia.

Disclosures: Samantha A. Schrier Vergano, MD, is a member of the Scientific Advisory Board for Ambry Genetics but has received no compensation for this work. No other authors have any conflicts of interest to disclose.

REFERENCES

- Rogers DG, Nasomyont N. Growth hormone treatment in a patient with Hurler-Scheie syndrome. J Pediatr Endocrinol Metab. 2014;27(9-10):957-960.

- Clarke LA, Wraith JE, Beck M, et al. Long-term efficacy and safety of laronidase in the treatment of mucopolysaccharidosis I. Pediatrics. 2009;123(1):229-240.

- Muenzer J, Wraith JE, Clarke LA, International Consensus Panel on Management and Treatment of Mucopolysaccharidosis I. Mucopolysaccharidosis I: management and treatment guidelines. Pediatrics. 2009;123(1):19-29.

- Raiman J, D'Aco K. An 8-year-old girl with a history of stiff and painful joints. Pediatric Ann. 2014;43(8):307-309.

- Beck M, Arn P, Giugliani R, et al. The natural history of MPS I: global perspectives from the MPS I Registry. Genet Med. 2014;16(10):759-765.

- Bevan WP, Hall JG, Bamshad M, Staheli LT, Jaffe KM, Song K. Arthrogryposis multiplex congenita (amyoplasia): an orthopaedic perspective. J Pediatr Orthop. 2007;27(5):594-600.

- White KK. Orthopaedic aspects of mucopolysaccharidoses. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2011;50 Suppl 5:v26-v33.

- Aldenhoven M, Sakkers RJ, Boelens J, de Koning TJ, Wulffraat NM. Musculoskeletal manifestations of lysosomal storage disorders. Ann Rhem Dis. 2009;68(11):1659-1665.

- Pastores GM, Meere PA. Musculoskeletal complications associated with lysosomal storage disorders: Gaucher disease and Hurler-Scheie syndrome (mucopolysaccharidosis type I). Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2005;17(1):70-78.

- Wraith JE, Clarke LA, Beck M, et al. Enzyme replacement therapy for mucopolysaccharidosis I: a randomized, double-blinded, placebo-controlled, multinational study of recombinant human alpha-L-iduronidase (laronidase).J Pediatr. 2004;144(5):581-588.

- Sifuentes M, Doroshow R, Hoft R, et al. A follow-up study of MPS I patients treated with laronidase enzyme replacement therapy for 6 years. Mol Genet Metab. 2007;90(2):171-180.