A Swollen Shoulder and A History of TB Exposure

An 18-month-old black male, native-born American infant residing in the inner city was brought to the emergency department complaining of a swollen right shoulder.

History

The mother denied any significant past medical history including trauma, fevers, malaise, or behavioral changes. The mother stated that during the past 4 to 5 months, the child had been using the right arm less. He was previously seen at least 2 times in an urgent care for this complaint. The mother stated that an x-ray of the extremity was obtained and was read as normal. The child’s immunizations were not up-to-date.

RELATED CONTENT

Can You Identify These Masqueraders?

Spondyloarthropathies: Update on Diagnosis and Therapy

Physical Examination

On the day of presentation, the child was noted to be alert, active, and throwing toys with both upper extremities. Vital stats included a temperature of 37.1ºC, heart rate of 160 beats per minute, respiratory rate 28 breaths per minute, and a weight 13.5 kg. On physical examination, the right shoulder was warm, tender, and erythematous. Peripheral pulses were intact, no other joint/skin involvement was noted, and lungs were clear to auscultation.

Laboratory Tests and Imaging

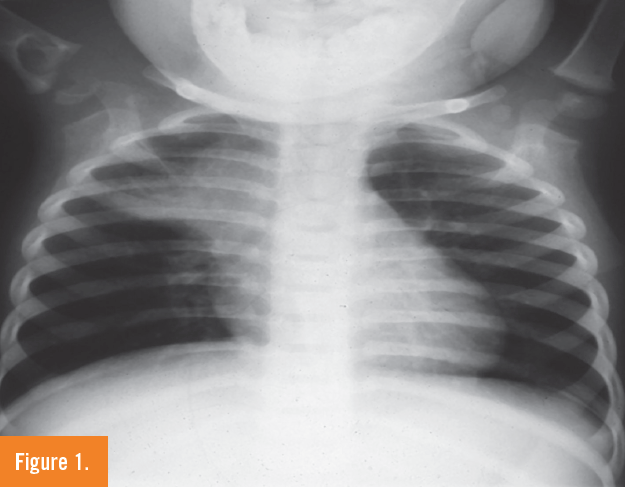

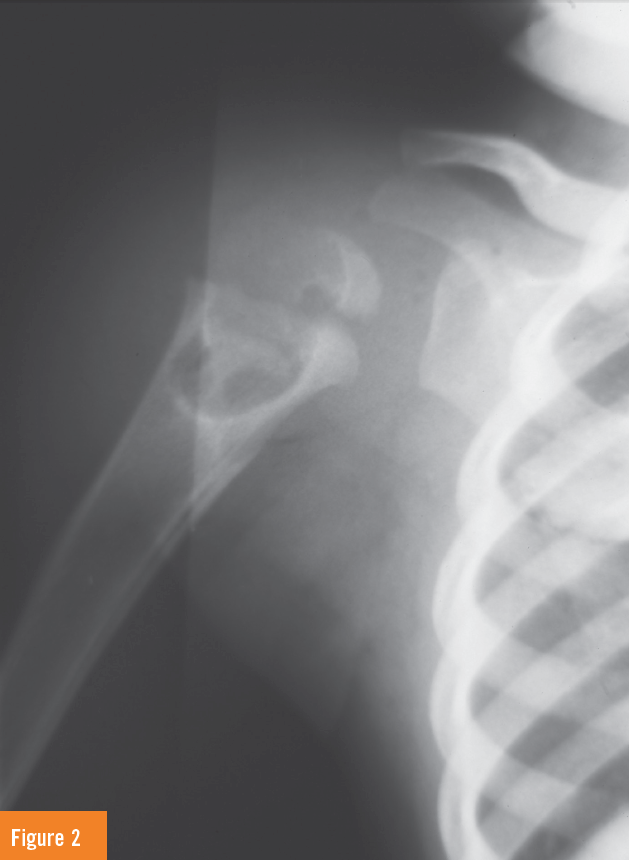

X-ray findings of the right shoulder demonstrated a large cystic lesion in the proximal humerus with a lytic process extending across the physis into the epiphysis proximally. An incidental large paratracheal lymph node was also noted both on the chest x-ray as well as the shoulder x-rays (Figures 1 and 2). This triggered the question of tuberculosis exposure by the pediatric and infectious disease consultants.

The white blood cell count (WBC) was 15,800/µL with no left shift, hematocrit was 26.9%, and electrolytes, BUN, creatinine, and glucose were normal.

Orthopedics surgery and pediatric infectious diseases were consulted. The patient underwent an ultrasound-guided aspiration and a large amount of purulent-appearing fluid was aspirated. Gram stain of the fluid revealed few PMN’s and no organisms. WBC of the fluid was 34,000/µL.

The patient was taken to the operating room by orthopedics for open irrigation, debridement, and biopsy. Intraoperatively, the bone was extensively destroyed with near total destruction of the physeal plate with a large amount of purulence noted.

What’s Your Diagnosis?

(Answer and discussion on next page)

Answer: Skeletal tuberculosis

Upon further questioning by the pediatric infectious diseases doctor about any history of TB exposure, the mother admitted that her son was exposed around a year ago to her uncle who had pulmonary TB. She said that her son was not screened for TB by the county TB clinic and did not receive isoniazid (INH) preventive therapy.

A tuberculin skin test was placed (TST) on the child that was positive with 20 mm of induration. The acid-fast bacillus (AFB) stain on the synovial fluid was negative, but the rhodamin-auramine stain was positive. A pathological specimen that was sent from surgery was positive for AFB on Ziehl-Neelsen stain. Pathology was positive for necrotizing granulomatous inflammation consistent with TB osteomyelitis and arthritis.

Discussion

TB osteomyelitis in children in developed countries is very unusual. In the late 1990s, the incidence in developed countries was in the range of 0.3 to 1.0 cases per 10,000 per year.1 An upsurge in cases (particularly with spinal involvement) in young immigrants in parts of Europe in the 1980s, particularly from Asia, was noted in the late 1980s.2 Osteoarticular involvement in several studies highlighted the following sites of involvement (in decreasing order of frequency): spine, hip, sternoclavicular joint/knee, radius/ulna, foot/ankle, elbow, shoulder, and ribs. 1-3

Agarwal and colleagues,4 in their study of the clinicosocial aspects of osteoarticular TB in a city in northern India, found the disease to be relatively common in the first and second decades of life, with decreasing incidence in the elderly—the opposite of developed countries. Shoulder involvement was rare.

Autzen and Elberg2 discovered that 70% of Danish patients with tuberculous bone and joint pathology between 1972 and 1984 had no previous history of TB, and only 20% had active pulmonary TB at the time of diagnosis.

Chronic pain, swelling, impaired range of motion, deformities, sinuses, and cold abscesses were commonly found in long-standing chronic disease. Onset of disease was insidious in 94% of patients with an average delay of 12 months to 19 months post-onset of disease and diagnosis.4

Dolberg et al noted extrapulmonary TB accounted for 33% of all the new cases of tuberculosis identified in the past decade in Beer Sheva, Israel.3 Bone and joint involvement accounted for 85 of the cases, with genitourinary TB accounting for 54%.1 Heterogeneity in this population was felt to be a major contributor to the incidence of extrapulmonary TB seen.

With the current resurgence of TB noted in the United States, particularly among the homeless, indigent, immigrant, or AIDS patient, a high index of suspicion must be maintained for TB etiology of joint pathology.

Outcome of the Case

Eventually, the bone and synovial fluid were positive for a drug sensitive TB culture. The child was initially started on daily isoniazid, rifampin, pyrazinamide, and streptomycin . Streptomycin was stopped when the sensitivity results were available. A follow-up shoulder x-ray at 1 month demonstrated improvement of the lytic lesion (Figure 3). He eventually received 2 months of 3 drug therapies—isoniazid, rifampin, and pyrazinamide—and completed a year’s course of therapy with isoniazid and rifampin under the supervision of the county TB program’s direct observation therapy and did very well.

Take-Home Message

1. Tuberculosis continues to be a worldwide health problem. In developed countries, skeletal tuberculosis had declined steadily.1,2 However, recent studies from North America, Europe, and New Zealand demonstrate a leveling off of this trend.1-3 Moreover, children very rarely present with bone or joint involvement.

2. Consideration for TB osteoarthritis should be entertained in children presenting with nonacute, prolonged history of nonspecific bone and joint complaints—especially if they have history of contact with individuals with active TB, as well as in the high risks groups, such as the indigent, homeless, immigrant, or AIDS patient.

3. Close contacts to contagious TB cases need to be immediately identified and tested for TB. If young children have been identified to have previously been in contact with TB, they need to be followed up and placed on INH preventive therapy to prevent long term TB morbidity. In this case, the county TB clinic should have detected the child’s exposure to TB by contact investigation of the uncle and should have receivedINH prophylaxis, thus preventing this complication.

4. The relatively low incidence of skeletal tuberculosis results in a risk of delayed diagnosis with dramatic increase in patient morbidity. Changing TB patterns require reassessment of populations at risk, including the very unusual finding of skeletal TB in native-born American children.

Laila Wilbur Powers, MD, is a staff physician at the Yampa Valley Medical Center in Steamboat Springs, CO.

Nazha Abughali, MD, is an associate professor of pediatrics at Case Western Reserve University, and a staff physician in the department of pediatrics at the MetroHealth Medical Center in Cleveland, OH.

Frits van der Kuyp, MD, MPH, is an associate professor emeritus at Case Western Reserve University and former controller for tuberculosis in Cuyahoga County, Cleveland, OH.

David Effron, MD, is an assistant professor of emergency medicine at Case Western Reserve University, attending physician in the department of emergency medicine at the MetroHealth Medical Center, and consultant emergency physician at the Cleveland Clinic Foundation, all in Cleveland, OH.

References:

1.Dolberg OT, Schlaeffer F, Greene VW, Alkan ML. Extrapulmonary tuberculosis in an immigrant society: clinical and demographic aspects of 92 cases. Rev Infect Dis. 1991;13(1):177-179.

2. Autzen B, Elberg JJ. Bone and joint tuberculosis in Denmark. Acta Orthopaedica Scandinavica. 1988;59(1):50-52.

3. Enarson DA, Fujii F, Nakielna EM, Grzybowski S. Bone and joint tuberculosis: a continuing problem. Can Med Assoc J. 1979;120(2):139-145.

4. Agarwal RP, Mohan N, Garg RK, et al. Clinicosocial aspect of osteoarticular tuberculosis, J Indian Med Assoc. 1990;88(11):307-309.

Additional recommended reading:

1. Gillespie WJ. Epidemiology in bone and joint infection. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 1990;4(3):361-376.

2. Gillespie WJ, Mayo KM, Johnstone V. Skeletal tuberculosis in New Zealand since the introduction of chemotherapy. Aust N Z J Surg. 1987;57(10):727-732.

3.Rathakrishnan V, Mohd TH. Osteo-articular tuberculosis. A radiological study in a Malaysian hospital. Skeletal Radiol. 1989;18(4):267-272.

4.Shannon FB, Moore M, Houkom JA, Waecker NJ Jr. Multifocal cystic tuberculosis of bone. Report of a case. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1990;72(7):1089-92.