Lepromatous Leprosy With Erythema Nodosum Leprosum

Authors:

Megha D. Patel, BS, Krupa Daniel, DO, and Shubhra Shetty, MD, FACP

Citation:

Patel MD, Daniel K, Shetty K. Lepromatous leprosy with erythema nodosum leprosum. Consultant. 2015;55(4):300-301.

One of the oldest-known infectious diseases in history, leprosy is caused by Mycobacterium leprae, the same family as the bacteria that cause tuberculosis (Mycobacterium tuberculosis). M leprae grow slowly and mainly affect the skin, nerves, and mucous membranes. It can also affect the eyes, muscles, bones, and testes. Though uncommon in the United States (most adults are actually immune from getting the disease), it is widespread globally and remains an important cause of peripheral neuropathy, particularly in poor communities. Despite its long-standing stigma, when identified early, leprosy’s impairments are treatable. Generally, diagnosis is via a skin biopsy of small lesions with treatment ranging from a few months to a few years depending upon the person and stage of the disease when diagnosed. According to a 2011 study by the National Hansen's Disease Program, armadillos are a possible source of infection in the southern United States.1 Leprosy stops being communicable just a few doses into treatment, which consists of standard antibiotics.

HISTORY

A 55-year-old white man presented with sores located on his hands, arms, and bilateral lower extremities. The sores started on his left hand 2 years ago and healed 2 weeks after onset. Over the next 3 months, the sores recurred, progressed to ulcerations, and turned black. The patient noted pain on ambulation as well as a 30-lb weight loss.

The patient had no significant past medical or surgical history. His medications included ciprofloxacin intravenous, methylprednisolone, aspirin, and mometasone nasal spray. He had worked as a landscaper in Florida and denied traveling outside of the United States. Though he admitted to a 35-year history of smoking, he had been alcohol-free for the past 15 years.

PHYSICAL EXAMINATION

On initial physical examination, the patient appeared malnourished. He had ulcerations on the tongue, coccyx, and bilateral upper and lower extremities. The remainder of his exam was unremarkable.

LABORATORY TESTING

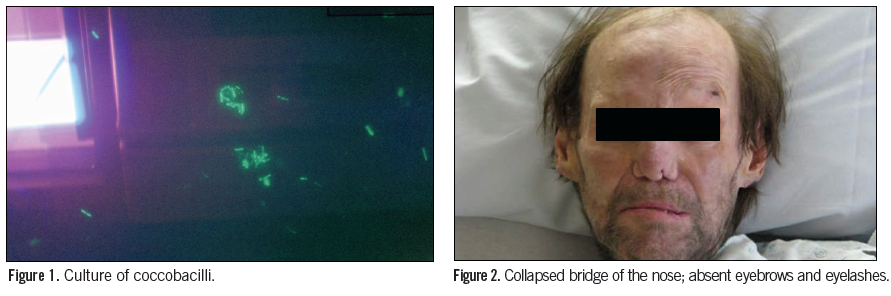

Initial laboratory results revealed a white blood cell count of 13.8 × 106 cells/L, along with 78% polymorphonuclear leukocytes, 13% lymphocytes, 8% monocytes, a low hemoglobin (12.2 g/L), and an elevated platelet count of 746,000/µL. The erythrocyte sedimentation rate was 60 seconds, alkaline phosphatase was 120 U/L, aspartate aminotransferase was 19 U/L, and alanine aminotransferase was 41 U/L. The patient was also antinuclear antibody and rheumatoid factor negative. A CT scan of the chest demonstrated a 6.2 mm calcified suprapleural nodular deformity. The skin biopsy revealed coccobacilli with a culture to follow (Figure 1).

TREATMENT

The patient was admitted to the hospital with a diagnosis of systemic vasculitis. Differential diagnoses included granulomatosis with polyangiitis, systematic lupus erythematosus, and anticardiolipid antibody syndrome. After consulting several departments, the infectious disease consult noted a collapsed bridge of the nose and absent eyebrows and eyelashes (Figure 2).The patient had a right-sided lower motor neuron facial palsy and clawed hands. He had necrotic and gangrenous skin lesions on the hands, legs, toes, and penis (Figure 3). With these findings, the differential now included lepromatous leprosy and endocarditis. A repeat skin biopsy revealed acid-fast bacilli, leading to the diagnosis of lepromatous leprosy (Hansen’s disease) with erythema nodosum leprosum (ENL).

The patient was immediately started on minocycline, and dapsone and rifampin were added soon after. With treatment and wound care, his lesions began to heal (Figure 4). Upon confirmation of ENL by The Hansen’s Disease Center, the minocycline was replaced with clofazimine.

The patient was immediately started on minocycline, and dapsone and rifampin were added soon after. With treatment and wound care, his lesions began to heal (Figure 4). Upon confirmation of ENL by The Hansen’s Disease Center, the minocycline was replaced with clofazimine.

The patient was treated for lepromatous leprosy for 2 years and is now considered leprosy-free. He is undergoing reconstructive surgery. The patient may have had exposure to armadillos in Florida while landscaping.

DISCUSSION

In North America, leprosy is a rare infectious disease caused by the bacterium M leprae. Between 1991 and 1995, 136 to 187 cases of leprosy were reported annually in the United States.2 While native to countries in Asia, Africa, and South America,3 it is endemic in areas like Texas, Hawaii, and Louisiana.1 Due to its rarity, leprosy can go undiagnosed leading to worsening complications including death.

Patients afflicted with lepromatous leprosy present with slightly hypopigmented or erythematous skin lesions with a smooth shiny surface. Most have a decreased ability to sweat and grow hair, as well as sensory deficits.2 Untreated lepromatous leprosy leads to nasal and facial deformities characterized by thick skin around the forehead, eyebrows, and cheeks, leading to the “lion-like” (leonine) facies.2,4

ENL is 1 of 2 common responses to M leprae. It involves a systemic inflammatory response to immune complex deposition in tissue space, blood, and lymphatic vessels.2,3,5

ENL patients typically present with a sudden onset of erythematous nodules on the face, extremities, or trunk. Additionally, many experience fever, malaise, and sensory and motor neuropathy.7 Patients can also present with arthralgias, iritis, vasculitis, orchitis, lymphadenitis, and dactylitis.2,3

Leprosy is diagnosed by clinical suspicion and confirmed with bacteriology and histology, which show acid-fast bacilli and noncaseating granulomas, respectively. It is commonly treated with dapsone, rifampicin, and clofazimine, although quinolones and macrolides are also used.6

Most commonly, leprosy is spread via human-to-human contact through nasal droplets. One-third of leprosy cases in the United States have no known exposure to leprosy, rather these cases have been attained through local sources of infection, not foreign sources. However, as noted earlier, leprosy is also associated with exposure to armadillos,5 natural reservoirs for the same strain of M leprae that is found in infected patients in the southern United States.8

With an average incubation period of 6 years (but can be as long as 40 years4,5), household contacts should be monitored carefully. New skin lesions should be reported. Younger contacts are given prophylactic rifampicin for 6 months.3

In the United States, diagnosis of leprosy is often delayed secondary to failure of recognition. Though this disease is curable, patients have severe morbidity and mortality due to improper recognition and failure to treat. Therefore, physicians should consider leprosy in the differential diagnosis for patients with cutaneous lesions and possible exposure to infected individuals or armadillos.

Megha D. Patel, BS, is a third year medical student at The Commonwealth Medical College in Scranton, PA.

Krupa Daniel DO, is a first year Infectious Disease Fellow at Newark Beth Israel Medical Center in Newark, NJ.

Shubhra Shetty, MD, FACP, is an Infectious Disease specialist and Regional Associate Dean at The Commonwealth Medical College in Scranton, PA.

References:

1. National Hansen's Disease (Leprosy) Program. US Department of Health And Human Services Website.

www.hrsa.gov/hansensdisease. Published 2011. Accessed April 6, 2015.

2. Boggild AK, Keystone JS, Kain KC. Leprosy: a primer for Canadian physicians. CMAJ. 2004;170(1):71-78.

3. Britton WJ, Lockwood DN. Leprosy. Lancet. 2004;363(9416):1209-1219.

4. Kustner EC, Cruz MP, Dansis CP, et al. Lepromatous leprosy: A review and case report. Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal. 2006;11:E474-9.

5. Moschella SL. An update on the diagnosis and treatment of leprosy. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004;51(3):417-426.

6. Mandell GL, Bennet JE, Dolin R. Principles and Practice of Infectious Diseases. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Churchill Livingstone; 1995.

7. Scollard DM, Adams LB, Gillis TP, et al. The continuing challenges of leprosy. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2006;19(2):338-381.

8. Truman RW, Singh P, Sharma R, et al. Probable zoonotic leprosy in the southern United States. N Engl J Med. 2011;364(17):1626-1633.