A Collection of Foreign Body Ingestions and Insertions

Coin Ingestion

Ron Shaoul, MD

A 7-year-old girl was brought to the emergency department because of moderate pain on swallowing and mild upper abdominal discomfort.

A few hours earlier, she had been given a piggy bank in order to save money for a family trip that had been planned for the next day. On shaking the piggy bank upside down above her head, a few coins fell out. The child admitted to having swallowed a coin.

Physical examination findings were unremarkable. A plain abdominal radiograph showed what appeared to be 1 coin in the girl’s stomach (Figure 1). Because the child and her family were to have traveled the next day, the decision was made to retrieve the foreign body. During an upper endoscopy procedure, 2 coins were located in the body of the stomach (Figure 2). They were retrieved with an endoscopic retrieval device without complication.

Most coin ingestions occur in children between 6 months and 3 years of age.1 Once the coins pass the gastroesophageal junction, they usually progress through the remainder of the gastrointestinal tract without difficulty in children with normal anatomy.2 If more than 1 coin or any other foreign body is suspected to have been ingested, a lateral abdominal radiograph also may be obtained.

References:

- Metzl K. Question from the clinician: coin ingestion. Pediatr Rev. 2003; 24(11):395.

- Conners GP. Management of asymptomatic coin ingestion. Pediatrics. 2005;116(3):752-753.

Light Bulb Ingestion

Robert M. Siwiec, MD, and Marc S. Fine, MD

A 74-year-old man with Parkinson disease dementia presented with constipation and bloating associated with abdominal pain.

An abdominal radiograph showed what appeared to be a small light bulb in the left upper quadrant (Figure 1). This image was compared with a film of the same patient, obtained 3 years earlier, which also had shown a foreign body (Figure 2). There was no mention of this object in the accompanying radiology report. A computed tomography scan of the abdomen revealed a metallic foreign body (approximately 2.3 × 1.2 cm) in the region of the descending portion of the duodenum.

An upper endoscopy procedure was performed. The foreign body was located in the bulb of the duodenum and was retrieved intact with a basket and overtube (Figure 3).

The specimen was identified as a broken light bulb (Figure 4), with a 1 × 1-cm glass portion and 1.2 × 0.7-cm metallic portion. At follow-up, the patient’s gastrointestinal tract symptoms had diminished.

According to his wife, the patient enjoyed taking flashlights and flashbulbs apart and putting them back together. It is possible that he had been holding the light bulb between his teeth while he worked and had accidentally ingested it.

Toothbrush Ingestion

Adela Spalter, MD

A 16-year-old girl of normal weight for height (body mass index, 21 kg/m2) was evaluated for a 6-month history of binge-purge cycles and amenorrhea. She met the diagnostic criteria for bulimia nervosa and had begun treatment that involved a multidisciplinary team.

During the second month of therapy, the patient presented to the emergency department after having accidentally swallowed a toothbrush while trying to induce vomiting with the brush’s handle.

Anteroposterior and lateral chest films showed 4 parallel rows of short metallic densities, which represented the metallic plates connected to the bristles.

The head of the toothbrush was in the cardiac part of the stomach. The location of the toothbrush handle could not be established. The patient was given general anesthesia; an esophagoscopy with a rigid fiberoptic instrument was performed, and the toothbrush was successfully removed.

In patients with bulimia, repetitive vomiting may cause swelling of the salivary glands, hoarseness, dental erosion, and throat irritation or lacerations. Self-induced vomiting often is concealed and thus is difficult to detect; however, it may result in injury such as abrasions on the dorsum of the hand. Most reports of accidental toothbrush ingestion have involved adolescent girls who had an eating disorder.1-4

Many complications secondary to bulimia nervosa are related to poor eating habits, malnutrition, and binge-purge cycles. The accidental ingestion of a toothbrush or other foreign body is a rare but dangerous complication. Moreover, patients who use an object to induce vomiting are at risk for other serious health problems, such as pressure necrosis, gastritis, and esophageal or gastric perforation.

This patient recovered uneventfully; she ate 2 hours after the toothbrush was removed. Oral fluoxetine (40 mg/d) was prescribed: the patient’s binge-purge cycles promptly stopped, menses restarted the following month, and she maintained a normal weight.

References:

- Kirk AD, Bowers BA, Moylan JA, Meyers WC. Toothbrush swallowing. Arch Surg. 1988;123(3):382-384.

- Riddlesberger MM Jr, Cohen HL, Glick PL. The swallowed toothbrush: a radiographic clue of bulimia. Pediatr Radiol. 1991;21(4):262-264.

- Wilcox DT, Karamanoukian HL, Glick PL. Toothbrush ingestion by bulimics may require laparotomy. J Pediatr Surg. 1994;29(12):1596.

- Faust J, Schreiner O. A swallowed toothbrush. Lancet. 2001;357(9261):1012.

NEXT: Broken Needles in an Injection Drug User's Neck

Broken Needles in an Injection Drug User’s Neck

Igor Mamkin, MD

A 53-year-old man with a 30-year history of heavy injection drug use (10 to 15 bags of heroin per day) was hospitalized with fever (temperature, 39.2°C) and chills of 2 days’ duration. Infective endocarditis was diagnosed based on the results of 3 sets of blood cultures, which were positive for methicillin-sensitive Staphylococcus aureus.

Initially, the patient had injected heroin through the peripheral veins. After the veins in his arms, legs, chest, abdomen, and forehead had collapsed, he began injecting himself subcutaneously (“skin-popping”). As a result, his body was covered with numerous round, healed scars. After a search for better access, he had started to inject himself through the carotid artery and jugular vein.

He continued to use the same needles until they broke inside the skin. A detailed history revealed that he had had 5 pneumothoraces caused by “central vessel” injection, which had required hospitalization and chest tube insertion.

Soft tissue radiographs of the patient’s neck revealed at least 17 needles.

Broken needles in injection drug users are not uncommon. One study reported that up to 20% of injection drug users had experienced a needle breaking while injecting.1

Complications from broken needles can include abscess formation as well as laceration of the major arteries, which may lead to lethal bleeding complications and, as in this patient’s case, pneumothorax.

Be extra careful when examining patients with a history of injection drug use because of the risk of injury from broken needles buried within the soft tissues.

This patient’s hospital course was otherwise uneventful. He was treated with intravenous oxacillin, 1.5 g every 4 hours. No new murmurs or signs of congestive heart failure were noted.

He was discharged after 7 days from the hospital to a short-term rehabilitation facility, where he would complete the course of intravenous antibiotic therapy via a peripherally inserted central catheter.

Reference:

- Norfolk GA, Gray SF. Intravenous drug users and broken needles—a hidden risk? Addiction. 2003;98(8):1163-1166.

NEXT: Metallic Corneal Foreign Body With Rust Ring

Metallic Corneal Foreign Body With Rust Ring

Craig J. Huang, MD

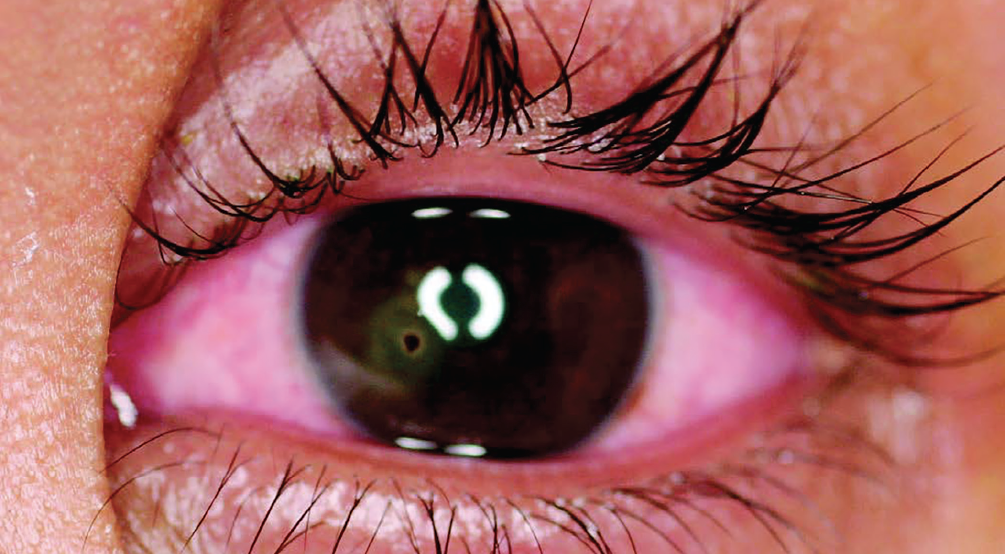

Two days after heading a soccer ball, a 17-year-old boy presented to the emergency department with progressive pain and a foreign-body sensation in his left eye.

Visual acuity was 20/20 in the boy’s right eye and 20/25 in the left eye. The pupils were equally round and reactive; full extraocular movements of both eyes were noted. The left eye had conjunctival injection and a 1-mm foreign body on the medial cornea with a surrounding halo of discoloration—typical of a metallic corneal foreign body.

A Seidel test (which demonstrates streaming of fluorescein dye from the aqueous humor when illuminated with UV light) revealed no evidence of corneal perforation; there were no areas of fluorescein dye uptake.

The patient was referred to an ophthalmologist for removal of the metallic corneal foreign body and rust ring. The patient had no evidence of an intraocular foreign body. The piece of metal might have been picked up by the surface of the soccer ball and then deposited on the patient’s cornea when he headed the ball. (Generally, grinding, drilling, or striking metal on metal are higher-risk activities for corneal foreign bodies.1) An antipolymicrobial ophthalmic ointment was prescribed for the resultant corneal epithelial defect.

Metallic foreign bodies must be removed promptly to prevent permanent corneal staining, which can develop within a few hours of embedding.2,3 Ophthalmologic consultation generally is recommended for removal of the foreign body and corneal rust ring. This often is performed under magnification with a slit lamp.4 The offending object can be removed with a tuberculin needle or foreign-body spud, and any rust staining can be extracted with an automated rust ring drill, brush, or burr.4 Complications of the foreign body can include corneal ulcer formation, perforation, and scarring.1,2

At follow-up, this patient had a small corneal stromal scar but no corneal staining. Visual acuity in his left eye had improved to 20/20-1.

References:

- Jones G. Foreign bodies in the eye. Accid Emerg Nurs. 1998;6(2):66-69.

- Bashour M. Corneal foreign body. eMedicine Web site. http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/1195581-overview. Updated March 5, 2014. Accessed February 3, 2016.

- Nagendran T. Management of foreign bodies in the emergency department. Hosp Physician. 1999;35(9):27-40.

- Smay J. Tools of the trade: a review. Optom Manag. April 2002. http://www.optometricmanagement.com/articleviewer.aspx?articleid=70418. Accessed February 3, 2016.