Peer Reviewed

Adult Intussusception

Author:

Merin Mathew, DO

NorthShore University HealthSystem, Evanston, Illinois

Citation:

Mathew M. Adult intussusception. Consultant. 2018;58(4):155-156.

A 59-year-old man presented to the emergency department (ED) with a 2-week history of severe bilateral lower abdominal pain. He also reported having large amounts of bright red blood in his stools along with diarrhea for the past 8 months, which had worsened over the past 2 weeks. He had a history of small-cell lung cancer (in remission after chemotherapy and radiation therapy approximately 17 years ago), non-small–cell cancer of the right lung (in remission after radiation therapy approximately 2 years ago), and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

Physical examination. In the ED, his vital signs were stable. On physical examination, he had normal bowel sounds with diffuse tenderness to palpation and voluntary guarding.

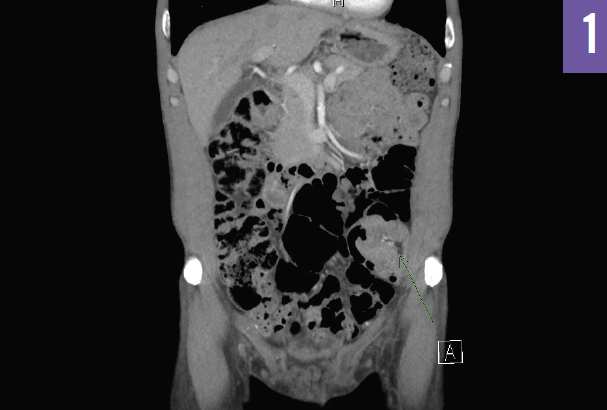

Diagnostic tests. Pertinent laboratory test results included a hemoglobin level of 9.1 g/dL (reference range, 13.0-17.0 g/dL), which had decreased from 13.2 g/dL 6 months ago. Computed tomography (CT) scans of the abdomen showed colocolic intussusception involving the distal descending colon, a finding suspicious for an underlying mass lesion (Figures 1 and 2). He underwent colonoscopy, which revealed a large, frond-like, villous, fungating, ulcerated, and friable mass in the sigmoid colon, partially obstructing the lumen. Biopsy results indicated colonic adenocarcinoma with negative margins and mesenteric lymph nodes negative for metastatic carcinoma.

Outcome of the case. The patient successfully underwent a laparoscopic sigmoid colon resection with end-to-end anastomosis and was discharged on postoperative day 5.

NEXT: Discussion

Discussion

Intussusception is one of the common causes of intestinal obstruction in children, but it is a relatively rare condition in adults, accounting for only 1% to 3% of adult cases of intestinal obstruction,1 and with an organic lesion present in the intussusception in 70% to 90% of cases.2 In children, intussusceptions are typically primary or idiopathic, but in adults they more commonly result from an underlying pathologic process that gives rise to a lead point. Intussusception occurs when the proximal segment of the bowel (intussusceptum) is pulled forward by normal peristalsis, causing telescoping or prolapse of the affected segment into the adjacent distal bowel (intussuscipiens).3

Intussusception can be classified based on location, etiology, and the presence or absence of a lead point.4 By location, intussusception is categorized as (1) enterocolic, confined to the small bowel; (2) ileocolic, in which the terminal ileum invaginates into the ascending colon; (3) ileocecal, in which the ileocecal valve is the lead point of the intussusception; or (4) colocolic, confined to the colon.5 By etiology, intussusception is classified based as primary (idiopathic) or secondary (benign or malignant lesion). Primary intussusception is more likely to occur in the small intestine, whereas secondary intussusception usually is associated with a pathological lead point. Adult intussusception occurs more frequently in the small bowel (50%-88%) than in the large bowel (12%-50%).4 In the small intestine, benign processes are predominant, whereas intussusception in the large intestine is more likely to have a malignant etiology.4 Adenocarcinoma is the most common cause of malignant large bowel intussusception, but lymphoma, lymphosarcoma, and leiomyosarcoma also have been reported causes.2

The clinical presentation of adult intussusception can vary, presenting a challenge to diagnosis. The classic presentation in the pediatric population—abdominal pain, “currant-jelly” stools, and a palpable abdominal mass—is rarely seen in adults. Intussusception in adults often presents with nonspecific signs of intestinal obstruction such as nausea, vomiting, intermittent abdominal pain, gastrointestinal tract bleeding, constipation, and abdominal distention. The authors of a report of a surgical series of 58 adults noted that guaiac test-positive stools or melena were seen more often than nausea, emesis, or abdominal pain in intussusceptions with malignant etiologies.6

Because of the nonspecific findings of intussusception, most patients are further evaluated with radiologic studies. Plain radiographs of the abdomen are usually the first diagnostic tool and may show signs of intestinal obstruction.7 Although ultrasonography is the modality of choice in children, CT is the modality of choice in adults to make the diagnosis, determine the underlying cause, and evaluate complications. A target-like lesion can be seen in the earliest stage, which progresses to a sausage-shaped mass representing mesenteric fat and bowel wall; a reniform mass (pseudokidney sign) due to bowel wall edema, mural thickening, and vascular compromise can be seen in the later stages.2 Colonoscopy is useful in cases where colonic involvement is suspected, since it allows the lesion to be simultaneously diagnosed and biopsied.4

In contrast to intussusception in children, which can be managed nonoperatively with air-contrast barium enemas, appropriate treatment in adults is controversial. Studies have shown that the surgical approach to adult intussusception depends on the location and the pathologic characteristics of the underlying lesion.6 Reduction before resection can allow a more limited resection but has the risk of intraluminal seeding or venous tumor dissemination.4 En bloc resection without reduction is recommended for colonic intussusception due its high malignancy rate (43%-100%), while reduction before resection may be preferable in enteric intussusception due its lower malignancy rate (1%-47%).4,8

The diagnosis of intussusception can be challenging in adults due to the nonspecific symptoms, and hence a high index of suspicion is needed for its early detection. Abdominal CT is a sensitive imaging modality used for the diagnosis of intussusception. Surgical intervention is often necessary because of the association of malignancy with adult intussusception.

REFERENCES:

- Demirkan A, Yağmurlu A, Kepenekci İ, Sulaimanov M, Gecim E, Dindar H. Intussusception in adult and pediatric patients: two different entities. Surg Today. 2009;39(10):861-865.

- Baleato-González S, Vilanova JC, García-Figueiras R, Juez IB, Martínez de Alegría A. Intussusception in adults: what radiologists should know. Emerg Radiol. 2012;19(2):89-101.

- Patel S, Eagles N, Thomas P. Jejunal intussusception: a rare cause of an acute abdomen in adults. BMJ Case Rep. 2014;2014:bcr2013202593.

- Akbulut S. Intussusception due to inflammatory fibroid polyp: a case report and comprehensive literature review. World J Gastroenterol. 2012;18(40):5745-5752.

- Marinis A, Yiallourou A, Samanides L, et al. Intussusception of the bowel in adults: a review. World J Gastroenterol. 2009;15(4):407-411.

- Azar T, Berger DL. Adult intussusception. Ann Surg. 1997;226(2):134-138.

- Gupta RK, Agrawal CS, Yadav R, Bajracharya A, Sah PL. Intussusception in adults: institutional review. Int J Surg. 2011;9(1):91-95.

- Chiang J-M, Lin Y-S. Tumor spectrum of adult intussusception. J Surg Oncol. 2008;98(6):444-447.