Peer Reviewed

Addressing DRESS: A Case of a Hydroxychloroquine-Induced Reaction

Authors:

Anandita Arora, MD; Mohamed Ali Mohamed, MD; and Andrew D. Thompson, MD, PhD

Citation:

Arora A, Mohamed MA, Thompson AD. Addressing DRESS: a case of a hydroxychloroquine-induced reaction. Consultant. 2017;57(11):648-650.

Drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms (DRESS) syndrome is a serious cutaneous drug reaction with potentially life-threatening implications. Anticonvulsants, allopurinol, sulfa drugs, and antibiotics including amoxicillin, vancomycin, and minocycline have been associated with cases of DRESS syndrome,1 but to our knowledge only a single case of hydroxychloroquine-induced DRESS syndrome has been reported previously.2 Presented here is the report of second case of a severe drug reaction associated with this commonly used drug, suggesting the need for increased vigilance with its use and to identify potentially critical implications of hydroxychloroquine treatment.

Case Report

A 59-year-old woman with hypothyroidism, who recently had received a diagnosis of Sjögren syndrome, was admitted to a hospital burn unit for an acute episode of a painful rash. She had been started on hydroxychloroquine and pilocarpine for Sjögren syndrome 12 days prior to the appearance of the diffuse, erythematous, maculopapular rash, which had begun on her head and face and had rapidly progressed to her trunk and hands. Her rheumatologist then discontinued hydroxychloroquine and started her on prednisone, but within the next 2 days, the rash had developed into tender pustules and vesicles.

At the time of admission, the rash had extended to her lower extremities, with marked swelling of both pinnae, but sparing the mucous membranes (Figures 1 and 2). The patient became febrile and developed atrioventricular nodal reentrant tachycardia from the marked systemic inflammatory response and severe peripheral vasodilatation.

Figure 1: Tender pustules and vesicles had spread across the patient’s body, including both legs.

Figure 2: The diffuse, erythematous, maculopapular rash had spread over both feet.

Along with a significant neutrophilic leukemoid reaction with left shift and toxic changes, her peripheral blood smear results also showed increased numbers of monocytes and eosinophils. Test results ruled out viral etiologies, including Epstein-Barr virus (EBV), human herpesvirus (HHV) 6 and 8, varicella-zoster virus, cytomegalovirus, and hepatitis. There was no hepatic or pulmonary involvement.

The differential diagnoses for such an acute exfoliative dermatitis included DRESS syndrome, Sweet syndrome, acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis (AGEP), and postviral syndrome.

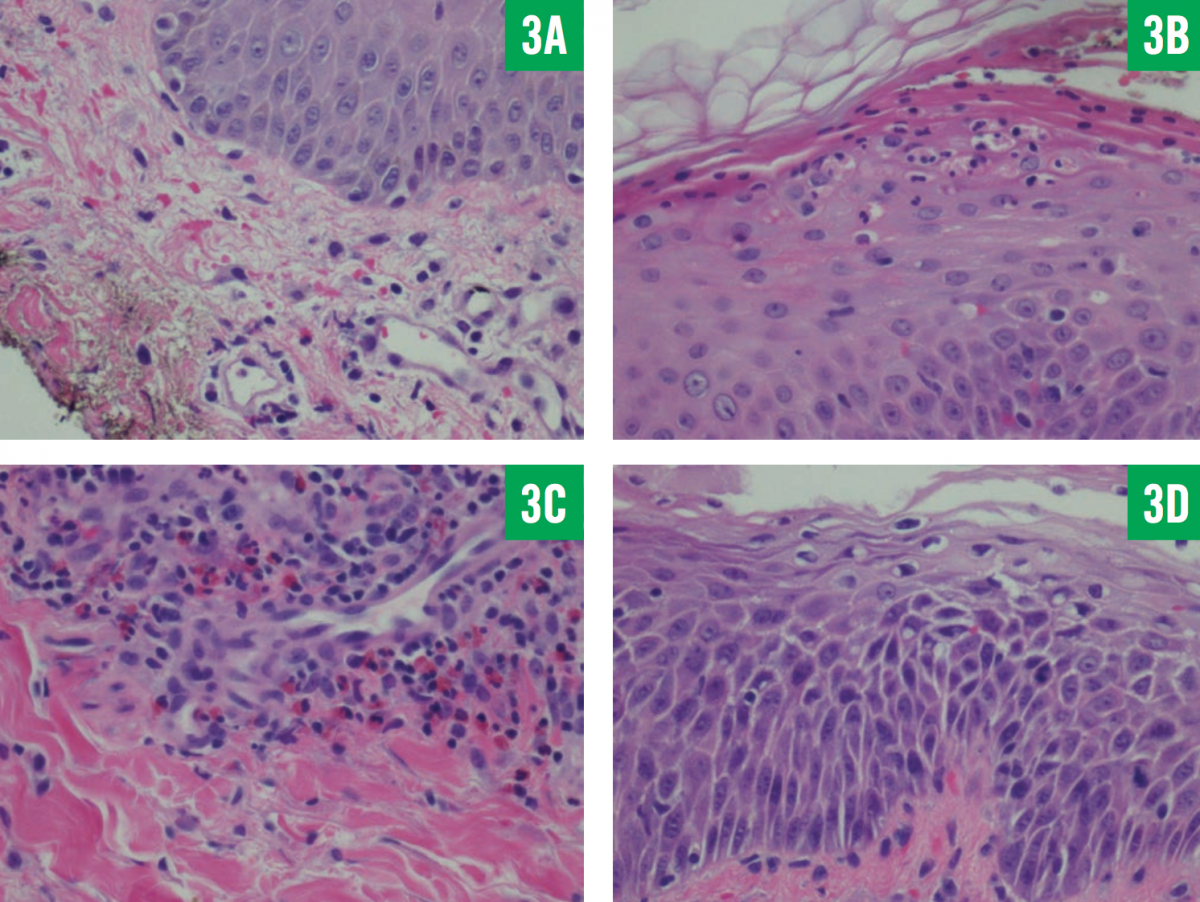

Skin biopsy results revealed spongiotic dermatitis with eosinophils and subcorneal neutrophils (Figure 3), a finding consistent with drug reaction with eosinophilia, confirming the diagnosis of DRESS syndrome secondary to hydroxychloroquine. The patient responded well after the discontinuation of hydroxychloroquine and the initiation of prednisone, 20 mg twice daily, with gradual desquamation of the rash over the next 10 days (Figure 4). She was discharged with a scheduled follow-up visit to a rheumatology clinic for a long-term corticosteroid taper; an alternative therapy for Sjögren syndrome was to be instituted when the episode of DRESS had resolved.

Figure 3: Skin biopsy results showed neutrophils in the stratum corneum and upper epidermis, with extravasation of blood vessels and the presence of dermal edema (A); neutrophils in the stratum corneum and red blood cells in the epidermis (B); eosinophils and lym- phocytes in abundance (C); and extensive spongiosis (D) (hematoxylin-eosin, ×400).

Figure 4: Gradual desquamation of the patient’s skin occurred after hydroxychloroquine was withdrawn and corticosteroid treatment was initiated.

Discussion

DRESS syndrome has been known for many decades as a severe adverse reaction to a medication—particularly allopurinol, anticonvulsants, and sulfa-containing antibiotics.1 After exposure to the offending drug, a latent period of approximately 2 weeks to 2 months before the onset of rash, fever, and multisystem involvement is the hallmark of DRESS syndrome.3 At the outset, the presentation often is similar to other drug exanthems and immune reactions owing to overlapping pathophysiologic mechanisms. The most frequently noted cutaneous manifestation of DRESS is skin pigmentation.

DRESS syndrome has been reported to be fatal with multiorgan failure in 10% to 40% of cases.4,5 Recently, DRESS syndrome has been classified as a delayed-type IVb hypersensitivity reaction to drugs and viruses, involving mainly type 2 helper T cells.6

The highly variable and broad clinical spectrum of DRESS syndrome makes early recognition and treatment important. The rash may be maculopapular initially, often associated with pruritus and facial edema, and can progress rapidly to diffusely painful pustules and vesicles. The initial presentation also includes fever and atypical lymphocytosis on blood smear results. Eosinophilia, although thought to be very common,5 may not appear early in the course of the syndrome.7 The liver is most commonly affected; however, kidney failure from interstitial nephritis or prerenal azotemia, as well as interstitial lung disease, myocarditis, and hemophagocytic syndrome, may also occur.

Our patient had fever and neutrophilic leukocytosis with acute kidney injury from a prerenal cause due to marked systemic inflammatory response and vasodilatation, with mild elevation of her prothrombin time (13.7 s; reference range, 9.4-11.7 s). Despite the discontinuation of hydroxychloroquine, she continued to worsen during the initial course of the disease—a frequent paradoxical observation that necessitates timely initiation of treatment.8 Several viruses, including HHV-6 and EBV, are implicated in the physiologic mechanism of DRESS syndrome and act via viral reactivation or the resultant strong antiviral immune response; thus, their presence has been considered among some proposed diagnostic criteria for DRESS syndrome.9

Hydroxychloroquine is known to cause other cutaneous reactions, which, like DRESS syndrome, are of the delayed type, including AGEP, toxic epidermal necrolysis, contact dermatitis, and photoallergic dermatitis.10 AGEP presents very similarly to DRESS syndrome, only occasionally differentiated on the basis of earlier onset of signs and symptoms and marked neutrophilia, with skin biopsy the mainstay of definitive diagnosis.

Therapy for DRESS depends on the severity of manifestations; milder forms resolve spontaneously, whereas severe forms require local or systemic glucocorticoid therapy with a slow long-term taper. Life-threatening forms require intravenous immunoglobulin along with systemic glucocorticoid therapy. In case of viral detection, antiviral agents also may be initiated. Patients with DRESS syndrome also may develop autoimmune conditions and reactions resembling graft-versus-host disease, making careful follow-up crucial.11

Hydroxychloroquine is very commonly used in rheumatology, and patients are advised to stop the drug if a rash develops. However, often the drug reaction is misdiagnosed either as a flare of systemic lupus erythematosus or as another form of cutaneous reaction. It is therefore imperative to be aware of this potentially severe condition possibly associated with hydroxychloroquine.

Anandita Arora, MD, is a geriatrics fellow at Detroit Medical Center in Detroit, Michigan.

Mohamed Ali Mohamed, MD, is a rheumatology fellow at Detroit Medical Center in Detroit, Michigan.

Andrew D. Thompson, MD, PhD, is an assistant professor in the Department of Pathology at the Wayne State University School of Medicine in Detroit, Michigan.

References:

- Cacoub P, Musette P, Descamps V, et al. The DRESS syndrome: a literature review. Am J Med. 2011;124(7):588-597.

- Volpe A, Marchetta A, Caramaschi P, Biasi D, Bambara LM, Arcaro G. Hydroxychloroquine-induced DRESS syndrome. Clin Rheumatol. 2008;27(4):537-539.

- Descamps V, Ben Saïd B, Sassolas B, et al; Groupe Toxidermies de la Société Française de Dermatologie. Management of drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms (DRESS) [in French]. Ann Dermatol Venereol. 2010;137(11):703-708.

- Bocquet H, Bagot M, Roujeau JC. Drug-induced pseudolymphoma and drug hypersensitivity syndrome (drug rash with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms: DRESS). Semin Cutan Med Surg. 1996;15(4):250-257.

- Peyrière H, Dereure O, Breton H, et al; Network of the French Pharmacovigilance Centers. Variability in the clinical pattern of cutaneous side-effects of drugs with systemic symptoms: does a DRESS syndrome really exist? Br J Dermatol. 2006;155(2):422-428.

- Lerch M, Pichler WJ. The immunological and clinical spectrum of delayed drug-induced exanthems. Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol. 2004;4(5):411-419.

- Descamps V, Ranger-Rogez S. DRESS syndrome. Joint Bone Spine. 2014;81(1):15-21.

- Shiohara T, Inaoka M, Kano Y. Drug-induced hypersensitivity syndrome (DIHS): a reaction induced by a complex interplay among herpesviruses and antiviral and antidrug immune responses. Allergol Int. 2006;55(1):1-8.

- Shiohara T, Iijima M, Ikezawa Z, et al. The diagnosis of a DRESS syndrome has been sufficiently established on the basis of typical clinical features and viral reactivations. Br J Dermatol. 2007;156(5):1083-1084.

- Rojas Pérez-Ezquerra P, de Barrio Fernández M, de Castro Martínez FJ, Ruiz Hornillos FJ, Prieto García A. Delayed hypersensitivity to hydroxychloroquine manifested by two different types of cutaneous eruptions in the same patient. Allergol Immunopathol (Madr). 2006;34(4):174-175.

- Ushigome Y, Kano Y, Ishida T, Hirahara K, Shiohara T. Short- and long-term outcomes of 34 patients with drug-induced hypersensitivity syndrome in a single institution. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;68(5):721-728.