Severe Neck Pain Due to Crowned Dens Syndrome

An 81-year-old man presented to the emergency department with a 6-day history of severe neck pain and restricted head movement. He had presented 2 months earlier with similar complaints and was discharged with analgesics. He also reported migratory arthralgias, primarily in the left shoulder, right wrist, and right knee.

His past medical history included diabetes, hyperlipidemia, hypertension, coronary artery disease, renal insufficiency, and myelodysplastic syndrome. His medications were a beta-blocker, statin, aspirin, insulin, and darbepoetin alfa.

Results of the physical examination were notable for limited range of motion at the neck, left shoulder, right wrist, and right knee because of pain. He had pain on palpation of the right wrist and knee with swelling in both hands and wrists and moderate effusion and warmth of the right knee. He was neurologically intact, and vital signs were stable. His erythrocyte sedimentation rate was elevated at 134 mm/h with a C-reactive protein (CRP) level of 253 mg/L. Other analyses were consistent with his history of diabetes, renal disease, and myelodysplastic syndrome.

He was admitted for pain control and further evaluation. A non-contrast CT scan of the spine revealed moderate degenerative changes. An MRI scan of the spine suggested soft tissue edema along the anterior margin of the upper cervical spine. He was treated with intravenous antibiotics because of concern about possible soft tissue infection, but CT-guided biopsy of the prevertebral space was unrevealing. Results of a lumbar puncture were normal.

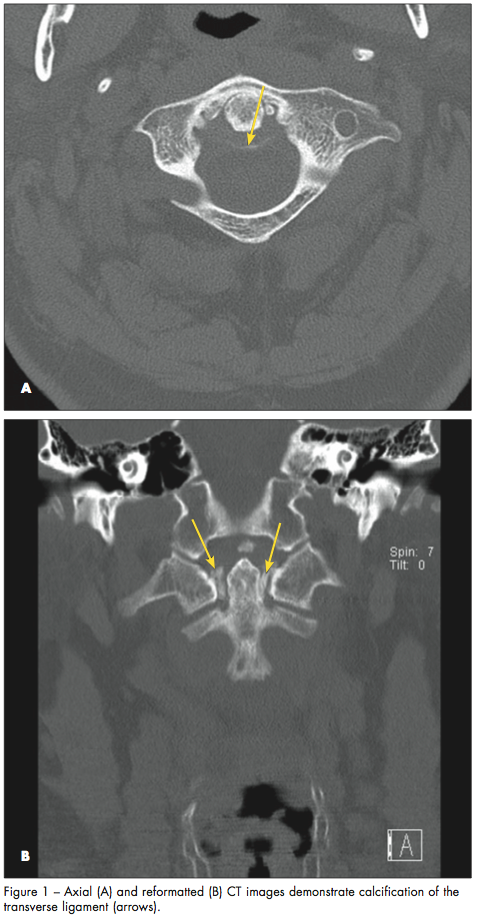

A rheumatology consultation was obtained. The consultants’ review of the initial CT scan of the spine noted transverse ligament calcification (Figure 1). A knee joint aspirate revealed calcium pyrophosphate crystals diagnostic of acute pseudogout (Figure 2).

CROWNED DENS SYNDROME: AN OVERVIEW

The patient’s clinical and radiographic findings, as well as knee joint aspirate, were consistent with the diagnosis of pseudogout, or calcium pyrophosphate crystal deposition disease (CPPD), of the cervico-occipital junction, also known as the crowned dens syndrome. The term derives from the crown-like density surrounding the odontoid process and was first coined in 1985.1 Fenoy and colleagues2 found that up to two thirds of patients with CPPD exhibit radiographic evidence of involvement of the cervical spine, but symptomatic involvement is relatively rare. Their analysis suggests a mean age at presentation of 70, with women being more likely than men to be affected.2 The presentation is usually acute. Typical symptoms and laboratory findings are severe neck pain with restriction of cervical rotation and a grossly elevated CRP level3; occasionally, fever is present. Crowned dens syndrome has been confused with giant cell arteritis, polymyalgia rheumatica, and meningitis, among other conditions.4

In this patient, the presence of peripheral joint inflammation ultimately led to the correct diagnosis and initiation of appropriate therapy. The inflammatory edema seen on MRI is typical, with calcifications visible only on CT.

MANAGEMENT

Patients with crowned dens syndrome may have spontaneous resolution of symptoms, but typical treatment for CPPD, including nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, colchicine, or a short course of corticosteroids, may result in more rapid improvement.1,4 Crowned dens syndrome does not require long-term corticosteroid therapy with gradual tapering, as does giant cell arteritis.

This patient was treated with a brief course of prednisone but was not given colchicine because of his renal insufficiency. Following initiation of prednisone, a rapid improvement in pain levels and inflammatory markers allowed for his discharge from the hospital.

1. Bouvet J, Le Parc J, Michalski B, et al. Acute neck pain due to calcifications surrounding the odontoid process: the crowned dens syndrome. Arthritis Rheum.1985;28(12):1417-1420.

2. Fenoy AJ, Menezes AH, Donovan KA, Kralik SF. Calcium pyrophosphate dehydrate crystal deposition in the craniovertebral junction. J Neurosurg Spine. 2008;8:22-29.

3. Siau K, Lee M, Laversuch CJ. Acute pseudogout of the neck—the crowned dens syndrome: 2 case reports and review of the literature. Rheumatol Int. 2011;31:85-88.

4. Aouba A, Vuillemin-Bodaghi V, Mutschler C, De Bandt M. Crowned dens syndrome misdiagnosed as polymyalgia rheumatica, giant cell arteritis, meningitis or spondylitis: an analysis of eight cases. Rheumatology.2004;43:1508-1512.