Preventing Falls in the Elderly

Your 75-year-old patient recently fell on the stairs in her home and sustained multiple contusions but no fractures. She had been living independently and was active in the community; however, she now has become fearful of falling again. What effective preventive measures can you offer her?

Falls are the leading cause of injury in persons age 65 and older.1 Each year about 30% to 40% of older adults sustain at least one fall.2,3

Falls are the leading cause of injury in persons age 65 and older.1 Each year about 30% to 40% of older adults sustain at least one fall.2,3

Although most falls do not cause serious injury, about 5% of persons who fall require hospitalization. Hip fracture is a leading cause of morbidity after a fall, and a significant percentage of patients who sustain a hip fracture never regain their baseline level of functioning. Accidents are the fifth leading cause of death in the elderly; falls are responsible for two thirds of these accidental deaths. About 75% of deaths attributable to falls occur in persons who are 65 years and older.1,3

The likelihood of falling and of being seriously injured in a fall increases with age. In 2009, the rate of fall injuries for adults 85 and older was almost 4 times that for adults 65 to 74.3 Persons age 75 and older who fall are 4 to 5 times more likely than those age 65 to 74 to be admitted to a long-term care facility for a year or longer.4

Falls that do not cause physical injury can still have adverse effects. Many of those who fall, even if they are not injured, develop a fear of falling. This fear may cause them to limit their activities, which can lead to reduced mobility. Falls are the largest single cause of restricted activity days among older adults.5

RISK ASSESSMENT

Recent guidelines from the US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) on the prevention of falls in older adults list several clinical factors that can be used to identify patients at increased risk for falling.6 Among these factors are:

•Older age.

•A history of mobility problems.

•A history of falls.

•Poor performance on the timed “Get-Up-and-Go” test.

The “Get-Up-and-Go” test is used to assess a patient’s balance and gait. The patient first sits in an armless chair about 10 ft from a wall. He or she then stands, walks toward the wall (using an assistive device if one is normally used), turns without touching the wall, returns to the chair, turns, and sits down. The observer notes any problems.7

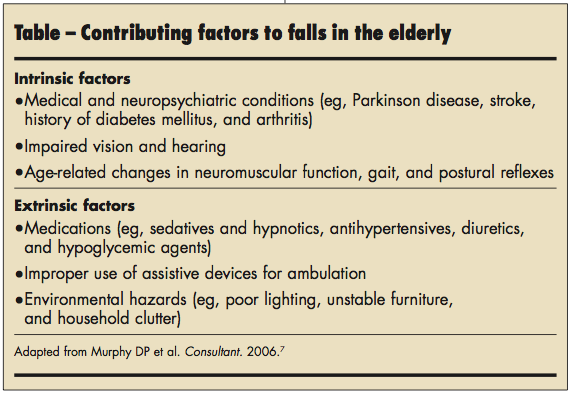

The USPSTF does not recommend routinely performing an in-depth risk assessment in community-dwelling adults aged 65 years or older because the benefit is likely to be minimal.6 The American Geriatrics Society recommends a multifactorial risk assessment for older adults who have had 2 falls in the past year, have gait or balance problems, or present with a recent history of a fall.8 The most effective components of the assessment are evaluations of balance and mobility, vision, and orthostatic or postural hypotension, as well as a review of medication use and home environment. Both intrinsic and extrinsic factors can contribute to an increased risk of falls in the elderly; these factors are listed in the Table. Follow-up and comprehensive management of identified risk factors are essential to the effectiveness of this strategy.

The evidence suggests that the impact of risk factors is cumulative. About 12% of patients with no risk factors or 1 risk factor will fall, whereas 75% of patients with 4 or more risk factors will fall.7

Keep in mind that your elderly patients may not report a fall to you. Unless they sustained a severe injury, such as a hip fracture or a subdural hematoma, many patients do not discuss falls. This reluctance stems from the following7:

•Patients may think that it is

“normal” for older persons to fall. Thus, they may feel that a fall is not worth mentioning to their health care provider.

•Patients may be afraid to tell their health care provider or their family members about a fall for fear of the consequences, particularly the possibility of placement in an assisted-living facility.

PREVENTION

To prevent falls in community-dwelling adults aged 65 years or older who are at increased risk, the USPSTF recommends exercise or physical therapy and vitamin D supplementation.6

Exercise or physical therapy. Seventeen trials (21 intervention arms) of exercise and physical therapy interventions showed a 13% decrease in the risk of falls; benefits were seen primarily among participants who were at increased risk for falling. Effective interventions included Tai Chi, group exercise classes, and at-home physiotherapy strategies that ranged in intensity from very low (9 hours or less) to high (more than 75 hours).9

Vitamin D supplementation. Supplementation was associated with a 17% reduction in the risk of falling during 6 to 36 months of follow-up in 9 trials reviewed by the USPSTF. The effect was even more pronounced in the studies that specifically targeted vitamin D-deficient older adults.9 The benefit from vitamin D supplementation occurred by 12 months; whether treatment of shorter duration is effective is unknown. The recommended daily allowance for vitamin D is 600 IU for adults aged 51 to

70 years and 800 IU for adults older than 70 years.6

Other interventions. Certain types of interventions were shown not to be effective. Four trials that addressed visual acuity and cataract correction among older adults found no reduction in falls. Two trials that studied hip protector use in high-risk older women showed no decrease in falls or fall-related injuries. Small single trials of medication management, protein supplementation, and behavioral counseling showed no benefit.9

1. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Injury Prevention and Control. Web-based Injury Statistics Query and Reporting System (WISQARS). http://www.cdc.gov/injury/wisqars/. Accessed July 16, 2012.

2. Hausdorff JM, Rios DA, Edelber HK. Gait variability and fall risk in community-living older adults: a 1-year prospective study. Arch Phys Med Rehab. 2001;82(8):1050-1056.

3. Hornbrook MC, Stevens VJ, Wingfield DJ, et al. Preventing falls among community-dwelling older persons: results from a randomized trial. Gerontologist. 1994:34(1):16-23.

4. Donald IP, Bulpitt CJ. The prognosis of falls in elderly people living at home. Age Ageing. 1999;28:121-125.

5. Vellas BJ, Wayne SJ, Romero LJ, et al. Fear of falling and restriction of mobility in elderly fallers. Age Ageing. 1997;26:189-193.

6. Moyer VA; on behalf of the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Prevention of falls in community-dwelling older adults: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med. 2012 May 28. [Epub ahead of print]

7. Murphy DP, Cleveland M. Falls: a preventable geriatric syndrome. Consultant. 2006;46(4):500-502.

8. American Geriatrics Society, British Geriatrics Society. 2010 AGS/BGS Clinical Practice Guideline: Prevention of Falls in Older Persons. New York: American Geriatrics Society; 2010. www.americangeriatrics.org/health_care_professionals/clinical_practice/clinical_guidelines_recommendations/2010/ Accessed July 16, 2012.

9. Michael YL, Lin JS, Whitlock EP, et al. Interventions to Prevent Falls in Older Adults: An Updated Systematic Review. Evidence Synthesis no. 80. AHRQ Publication no. 11-05150-EF1. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; December 2010.