Peer Reviewed

Pyoderma Gangrenosum With Systemic Symptoms Initially Misdiagnosed as Cellulitis

AUTHORS:

Misty M. Hobbs, BSc1 • Zachary H. Tarter, BSc1 • Chase L. Wilson, MD2

AFFILIATIONS:

1University of Kentucky College of Medicine, Lexington, Kentucky

2Elkhorn Dermatology, Georgetown, Kentucky

CITATION:

Hobbs MM, Tarter ZH, Wilson CL. Pyoderma gangrenosum with systemic symptoms initially misdiagnosed as cellulitis. Consultant. Published online May 14, 2020. doi:10.25270/con.2020.05.00019

Received January 13, 2020. Accepted April 30, 2020.

DISCLOSURES:

The authors report no relevant financial relationships.

CORRESPONDENCE:

Chase L. Wilson, MD, Elkhorn Dermatology, 304 Boston Sq, Georgetown, KY 40324 (drwilson@elkhorndermatology.com)

A 67-year-old woman with a history of irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) and diverticulitis presented to her primary care provider for evaluation of a leg wound.

Over the course of a few days, the patient had developed warmth, erythema, edema, pain, and tenderness of the left anterior lower leg. Cellulitis had been suspected, and she had been given a 7-day course of cephalexin, followed by clindamycin after the cellulitis had failed to improve. Bacterial wound cultures were obtained and ultimately were negative for bacteria.

A dermatologist was consulted, given the recalcitrance of the symptoms to antibiotics and the unusual clinical appearance of the lesions. On consultation, the patient reported having low-grade fevers, joint pain in her elbows and shoulders, and extreme pain of the involved left lower leg. Examination of the skin of the left shin revealed a violaceous, tender nodule with minimal serosanguineous drainage and surrounding ill-defined erythema (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Violaceous, tender nodule with minimal serosanguineous drainage and surrounding erythema on the patient’s left shin.

The differential diagnosis included pyoderma gangrenosum (PG), atypical mycobacterial infection, deep fungal infection, and Sweet syndrome. Two punch biopsies were performed; one specimen was sent for histologic evaluation, and the other for bacterial, atypical mycobacterial, and fungal tissue cultures.

Three days later, the patient developed worsening painful violaceous ulceration with undermined borders on the left shin and inferior abdomen, and new tender violaceous nodules and plaques on the dorsal left foot, right lower leg, and bilateral arms (Figures 2-6).

Figure 2. Worsening violaceous ulceration with undermined borders on the left shin.

Figure 3. Violaceous ulceration with undermined borders on the inferior abdomen.

Figure 4. New tender violaceous nodules on the dorsal left foot.

Figure 5. New tender, violaceous nodules on the right lower leg.

Figure 6. New tender, violaceous nodules on the arms.

Because of her primary care physician’s concern for progressive cellulitis, the patient was admitted to our community hospital. The biopsy specimen demonstrated purulent neutrophilic inflammation with perivascular lymphocytic inflammation and dermal fibroplasia, favoring a diagnosis of PG as opposed to cellulitis. A repeated biopsy was performed while the patient was hospitalized, with a final read of acute cellulitis; however, all blood and wound cultures ultimately returned negative for bacteria.

The skin lesions continued to worsen despite the administration of broad-spectrum intravenous antibiotics, and the patient’s interdisciplinary team agreed on a final clinical diagnosis of PG with systemic symptoms. Prednisone was started at 60 mg daily, which resulted in rapid resolution of her pain, fever, and joint pain. She was slowly tapered off prednisone as an outpatient, with complete remission of her skin lesions. Her symptoms began to flare when the prednisone dose reached 10 mg daily, and corticosteroid-sparing agents were discussed.

During the prednisone taper, the patient underwent a colonoscopy and was diagnosed with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), ultimately requiring surgical intervention, and she was lost to follow-up.

Discussion. PG is a rare neutrophilic dermatosis that classically presents as rapidly progressing red to violaceous cutaneous ulcers with undermined borders and a purulent base on the lower leg or abdomen. These lesions sometimes can manifest as a response to trauma, a phenomenon known as pathergy.1 Nonulcerative forms also exist, including peristomal, pustular, bullous, and vegetative PG.2

Systemic symptoms such as fever, malaise, arthralgia, and myalgia may be present, and PG may present as part of an autoinflammatory syndrome such as PAPA (pyogenic arthritis, PG, and acne), PAPASH (pyogenic arthritis, PG, acne, and hidradenitis suppurativa), or PASH (PG, acne, and hidradenitis suppurativa).2,3 Extracutaneous findings, most commonly pulmonary involvement, may also occur preceding, during, or following the appearance of skin lesions.4

The differential diagnosis for PG is wide and includes vascular occlusive or venous disease (venous stasis ulcers), vasculitis, leukemia cutis, primary cutaneous infection (cellulitis; deep fungal infection such as aspergillosis; cutaneous tuberculosis), drug-induced, or other inflammatory disorders (cutaneous Crohn disease).5

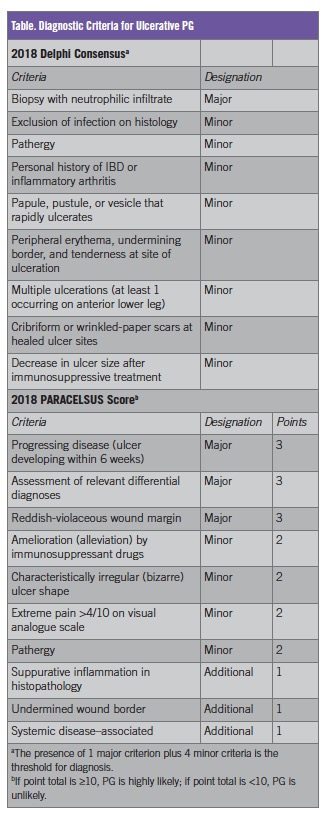

PG has long been considered a diagnosis of exclusion; however, a lack of objective diagnostic criteria likely contributes to frequent misdiagnosis. In 2018, two sets of validated diagnostic criteria were proposed, including the Delphi consensus criteria6 and the PARACELSUS score7 (Table). Notably, histologic rule-out of infection or assessment of relevant differential diagnoses is still included in these criteria.

As in our patient’s case, histopathologic findings are nonspecific and include a dense neutrophilic infiltrate without evidence of microorganisms on special stains and culture. Secondary leukocytoclastic vasculitis is present in approximately 40% of cases, and early lesions may show a deep suppurative folliculitis.8

Sweet syndrome is another prototypical neutrophilic dermatosis that has overlapping clinical and histopathologic findings with PG, although fever is more common, and ulceration is less likely.9 Both are frequently associated with multisystemic disorders, such as chronic autoimmune disorders (IBD, rheumatoid arthritis), myeloproliferative disorders (eg, acute myeloid leukemia), and solid malignancies.10

Immunosuppression (eg, systemic corticosteroids, infliximab) is the mainstay of treatment of PG, although no single, specific treatment exists, and only two controlled trials for treatment have been published.2

Because of its varied clinical morphology and presentation, nonspecific histopathology, and systemic symptoms mimicking infection, a high index of suspicion for PG must be maintained. Histopathologic findings are nondiagnostic and may mimic those of cellulitis. Thus, in nonresponsive cases of presumed cellulitis, such as the case presented here, PG should be considered, even if cellulitis has been “biopsy-confirmed.” Furthermore, a thorough review of systems including constitutional, gastrointestinal, pulmonary, and hematologic considerations should be performed in such cases. For example, our patient had a longstanding diagnosis of IBS and episodes of diverticulitis; following this presentation, she was diagnosed with IBD. Routine bloodwork, including a complete blood cell count, a comprehensive chemistry profile, urinalysis, and a hepatitis profile should be obtained to evaluate for an underlying systemic illness in cases of PG, and serum and/or urine protein electrophoresis and a peripheral smear should be ordered if indicated.

REFERENCES:

- McKenzie F, Arthur M, Ortega-Loayza AG. Pyoderma gangrenosum: what do we know now? Curr Derm Rep. 2018;7:147-157. doi:10.1007/s13671-018-0224-y

- Brooklyn T, Dunnill G, Probert C. Diagnosis and treatment of pyoderma gangrenosum. BMJ. 2006;333(7560):181‐184. doi:10.1136/bmj.333.7560.181

- Cugno M, Borghi A, Marzano AV. PAPA, PASH and PAPASH syndromes: pathophysiology, presentation and treatment. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2017;18(4):555‐562. doi:10.1007/s40257-017-0265-1

- Borda LJ, Wong LL, Marzano AV, Ortega-Loayza AG. Extracutaneous involvement of pyoderma gangrenosum. Arch Dermatol Res. 2019;311(6):425‐434. doi:10.1007/s00403-019-01912-1

- Weenig RH, Davis MDP, Dahl PR, Su WPD. Skin ulcers misdiagnosed as pyoderma gangrenosum. N Engl J Med. 2002;347(18):1412‐1418. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa013383

- Maverakis E, Ma C, Shinkai K, et al. Diagnostic criteria of ulcerative pyoderma gangrenosum: a Delphi consensus of international experts. JAMA Dermatol. 2018;154(4):461‐466. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2017.5980

- Jockenhöfer F, Wollina U, Salva KA, Benson S, Dissemond J. The PARACELSUS score: a novel diagnostic tool for pyoderma gangrenosum. Br J Dermatol. 2019;180(3):615‐620. doi:10.1111/bjd.16401

- Wollina U. Pyoderma gangrenosum—a review. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2007;2:19. doi:10.1186/1750-1172-2-19

- Lear JT, Atherton MT, Byrne JP. Neutrophilic dermatoses: pyoderma gangrenosum and Sweet’s syndrome. Postgrad Med J. 1997;73(856):65‐68. doi:10.1136/pgmj.73.856.65

- Vignon-Pennamen M-D. Sweet’s syndrome. In: Wallach D, Vignon-Pennamen M-D, Valerio Marzano A, eds. Neutrophilic Dermatoses. Springer International Publishing; 2018:13-35. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-72649-6_3