Peer Reviewed

Methicillin-Susceptible Staphylococcus aureus Pacemaker Lead Endocarditis

AUTHOR:

Paul C. Adjei, MD, MS1,2

AFFILIATIONS:

1Division of Geographic Medicine and Infectious Diseases, Tufts Medical Center, Boston, Massachusetts

2Tufts University School of Medicine Clinical and Translational Science Institute, Boston, Massachusetts

CITATION:

Adjei PC. Methicillin-susceptible Staphylococcus aureus pacemaker lead endocarditis. Consultant. 2021;61(12):e11-e14. doi:10.25270/con.2021.01.00009

Received June 11, 2020. Accepted November 9, 2020. Published online January 13, 2020.

DISCLOSURES:

The authors report no relevant financial relationships.

CORRESPONDENCE:

Paul C. Adjei, MD, Division of Geographic Medicine and Infectious Diseases, Tufts Medical Center, 800 Washington St, Box 238, Boston, MA 02111 (nkwakuadjei@gmail.com)

A 70-year-old man who had undergone pacemaker placement for atrial fibrillation 21 years ago, with a generator change 4 years ago, was transferred from an outside hospital to our hospital for evaluation of fever of unknown origin.

History. Approximately 5 months prior to presentation, he had been admitted to the outside hospital with community-acquired pneumonia (CAP), which had been treated empirically with ceftriaxone, 1 g once daily, and azithromycin, 500 mg once daily. At that admission, he had presented with 3 days of what he called “hots and colds” sensations and was found to be febrile (temperature, 38.3 °C); chest radiographs were suggestive of early right lower-lobe pneumonia. He had been an inpatient for 8 days and had been febrile most of that time, but sputum and blood cultures had remained negative for bacteria.

One week after discharge, his primary care physician had prescribed a 7-day course of doxycycline for persistent fevers.

Two weeks after discharge, the man was readmitted to the outside hospital with persistent fevers without localizing signs. There, he had undergone an extensive infectious diseases workup (blood, sputum, and urine cultures; Lyme disease, Anaplasma, Babesia, Bartonella, and Coxiella serology tests; a full respiratory viral panel; tests for atypical respiratory bacteria, Legionella, and pneumococcal urine antigens; HIV, cytomegalovirus, and Epstein-Barr virus tests; and a peripheral blood smear), the results of which had all been negative. Transesophageal echocardiography (TEE), performed to evaluate fevers in the presence of a pacemaker, reportedly had shown a mass (either a thrombus or a vegetation) on the right atrial pacemaker lead.

Given that finding, he had been transferred to our hospital, where TEE findings were negative for any lesion on the pacemaker leads or heart valves, and cultures remained negative for bacteria. He was discharged home on empiric ceftriaxone, 2 g once daily, and vancomycin, dosed to serum trough level of 15 to 20 µg/mL, for presumed culture-negative endocarditis.

Nevertheless, he again developed fevers, chills, and sweats a week after having completed his antibiotic regimen. He was again readmitted to the outside hospital and then was transferred to our hospital (the current admission) with a diagnosis of fever of unknown origin.

Current hospital course. Except for the fever, his physical examination findings were unremarkable, including examination of the pacemaker site. He had no diarrhea, weight loss, arthralgia, cellulitis at the pacemaker site, or rashes. He did not hunt, farm, or eat raw or undercooked meat.

At admission, blood cultures were positive for methicillin-susceptible Staphylococcus aureus (MSSA) and would remain positive for 7 days despite the patient’s regimen of oxacillin, 2 g every 4 hours, and even after being switched to daptomycin 8 mg/kg and ceftaroline, 600 mg every 8 hours. He remained persistently febrile in the 38.0 to 38.5 °C range without any localizing signs, he did not require intubation or vasopressor support, and he remained stable on room air.

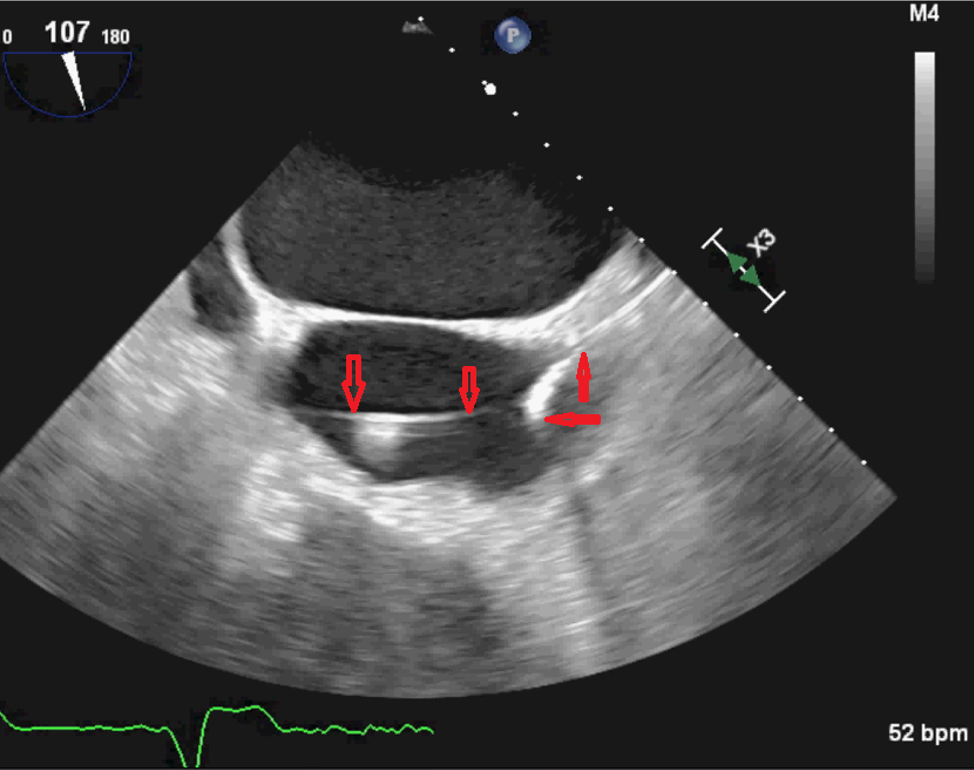

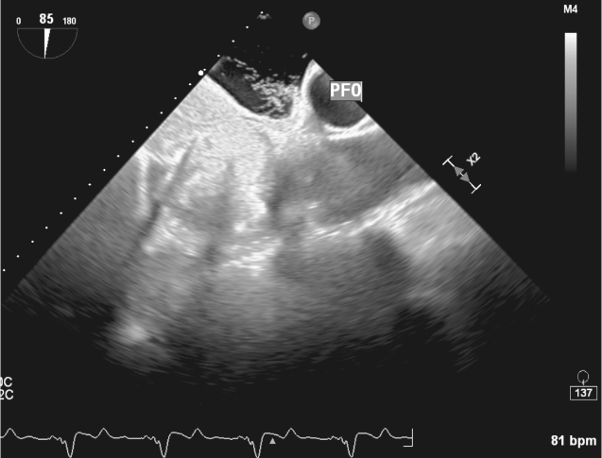

No embolic lesions were visualized on computed tomography (CT) scans of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis. TEE findings were negative for any lesions on the pacemaker leads or valves (Figure 1). However, given the lack of an alternative explanation for his persistent bacteremia, it was decided to extract the pacemaker. Intraoperative TEE revealed a patent foramen ovale (PFO) (Figure 2) and a thrombus in the left atrial appendage (Figure 3) but revealed no masses on the pacemaker leads or cardiac valves. However, during the extraction procedure, the superior vena cava leads were found to be encased in significant amounts of thrombus.

Figure 1. TEE image showing the right atrial lead (downward-pointing arrows) traversing the right ventricle on its way to the right atrium. The right ventricular lead is indicated by the upward-pointing and sideways-pointing arrows. No vegetations were present.

Figure 2. Intraoperative TEE image showing the PFO as labeled.

Figure 3. Intraoperative TEE image showing the left atrial appendage with a thrombus and surrounding sluggish blood flow.

Cultures of the right atrial lead with the thrombus grew MSSA with similar susceptibility patterns but different from blood and right ventricular lead isolates (Table). His blood cultures had become negative 1 day before extraction of the pacemaker (1 day after the switch from oxacillin to daptomycin and ceftaroline). The pacemaker pocket was nonpurulent at extraction and had no growth on cultures.

Table. Culture Results; Organism: MSSA | ||||

| Blood and RV Lead Isolate | RA Lead and Thrombus Isolate | ||

Antibiotic | MIC (µg/mL) | Interpretation | MIC (µg/mL) | Interpretation |

Oxacillin | 0.5 | Sensitive | 0.5 | Sensitive |

Gentamicin | ≤0.5 | Sensitive | ≤0.5 | Sensitive |

Ciprofloxacin | ≤0.5 | Sensitive | ≤0.5 | Sensitive |

Levofloxacin | 0.25 | Sensitive | 0.5 | Sensitive |

Moxifloxacin | ≤0.5 | Sensitive | ≤0.25 | Sensitive |

Erythromycin | ≥8 | Resistant | ≥8 | Resistant |

Clindamycin | NA | Resistant | NA | Resistant |

Daptomycin | 0.5 | Sensitive | Not tested | NA |

Vancomycin | 1 | Sensitive | 1 | Sensitive |

Doxycycline | ≤0.5 | Sensitive | ≤0.5 | Sensitive |

Tetracycline | ≤1 | Sensitive | ≤1 | Sensitive |

Rifampin | ≤0.5 | Sensitive | ≤0.5 | Sensitive |

TMP-SMX | ≤10 | Sensitive | ≤10 | Sensitive |

Abbreviations: MIC, minimum inhibitory concentration; MSSA, methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus; NA, not applicable; RA, right atrial; RV, right ventricular; TMP-SMX, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole. | ||||

The patient was discharged home on daptomycin through a right-arm midline catheter, 8 mg/kg once daily for 6 weeks from the day of pacemaker extraction. Oxacillin was discontinued because of difficult vascular access; he had received 16 days of oxacillin at this point.

At his 1-year follow-up visit, the patient was in good health.

Discussion. The cardinal rules of infectious diseases practice are identifying the infecting pathogen, identifying the source of infection, controlling the source of infection, and eradicating the infecting pathogen. But what happens when no pathogen is identified, and there are doubts about the source of infection?

Specifically in this patient’s case, the following questions arise:

• Should a diagnosis of culture-negative endocarditis be made in the presence of an intracardiac device (without evaluating the device)?

• Should the pacemaker have been explanted during the patient’s second hospitalization, when the initial TEE had revealed a possible mass on the lead?

• Could the initial lead vegetation have embolized, explaining why it was not seen on the repeated TEE after transfer to our hospital?

• Assuming that the patient had had lead endocarditis all along, could his initial CAP have been due to septic emboli?

• If the thrombus had embolized through his PFO, why was there was no evidence of systemic emboli on multiple imaging studies?

Blood culture–negative endocarditis may be a result of sterilization by previous antibacterial treatment (a scenario that may apply to our patient’s case), fastidious microorganisms in which prolonged incubation is necessary, or true culture-negative endocarditis due to intracellular bacteria that cannot be routinely cultured in blood with currently available methods.1

In the presence of a pacemaker, without evaluating the leads for infection, it is not possible to definitively diagnose culture-negative endocarditis, since lead culture and serology results may be positive in the absence of negative blood cultures—especially in a patient like ours, whose leads were later found to be infected. What, then, explains the negative findings on repeated TEE in our patient’s case? No pulmonary embolic lesions were visualized on CT scans. He had a PFO, but there was no clinical or radiographic evidence of systemic embolic events, so embolization could not have explained the findings. The decision to not explant the pacemaker was based on the negative results of TEE, which had been done in large tertiary referral center, and the fact that the patient was pacemaker-dependent.

Most of these questions cannot be answered after the fact; Occam’s razor would suggest that the patient’s protracted illness was a result of MSSA pacemaker endocarditis, since blood, leads, and thrombi all grew MSSA.

The final diagnosis in itself was not surprising, since S aureus (methicillin-resistant or -susceptible) is second only to coagulase-negative staphylococci in causing pacemaker endocarditis; together, these bacteria cause up to 75% of generator pocket infections and 89% of device-related endocarditis.2-5 However, given the subacute or even indolent nature of his disease course, the primary team questioned whether there was an alternative diagnosis, since S aureus infection typically causes aggressive disease with extensive damage to valves (perforation, abscess, and rupture). The disease course of our patient was consistent with that of lead endocarditis, which is comparable to right-sided endocarditis and mostly follows a subacute course regardless of etiology.3-6

Pacemaker infections come in 2 forms: pocket infection, which involves the subcutaneous pocket containing the generator and subcutaneous parts of the lead; and lead infection, which by definition is a right-sided endocarditis that may or may not involve the heart valves. Pacemaker lead endocarditis is a rare but serious complication of permanent transvenous pacing. Approximately 40% of patients do not have concomitant pocket infection (such as our patient).3-6 Blood cultures are positive in up to 90% of cases, with staphylococci identified in up to 94% of those cases.3-6 Clinical and/or radiographic evidence of pulmonary septic embolization occurs in a minority of patients (27%-38%).4,6 TEE demonstrates a vegetation or mass in up to 94% of cases.4,6

Treatment for MSSA pacemaker endocarditis involves antibiotic therapy; explantation of the pacemaker leads, residual leads, and pulse generator; and reimplantation if the indication for pacing still exists. Explantation must be done as soon as possible—early diagnosis and lead explantation within 3 days of diagnosis is associated with lower in-hospital mortality, with a 7-fold increase in 30-day mortality if the device is not removed.7 Retained leads are associated with 10-fold increased incidence of recurrent infections.7,8

The duration of antibiotic therapy for S aureus bacteremia with pacemaker lead endocarditis without valvular involvement is 4 to 6 weeks (6 weeks with valvular involvement).7 If still indicated, a new device can be implanted after at least 72 hours of negative blood cultures and after complete source control has been achieved, and is preferably located at the contralateral side. For pacemaker-dependent patients, temporary pacing is required as a bridge to reimplanting a new device.7

Returning to the question of culture-negative endocarditis during the early phase of this patient’s disease, he did receive antibiotics that have activity against bacterial causes of culture-negative endocarditis (ceftriaxone) during the first admission and before the second admission (doxycycline). A literature review yielded 2 cases of “culture-negative” pacemaker lead endocarditis—both patients eventually had blood cultures positive for Aggregatibacter aphrophilus.9,10

REFERENCES:

- Ebato M. Blood culture-negative endocarditis. In: Firstenberg MS, ed. Advanced Concepts in Endocarditis. IntechOpen; September 12, 2018. doi:10.5772/intechopen.76767

- Sohail MR, Uslan DZ, Khan AH, et al. Risk factor analysis of permanent pacemaker infection. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;45(2):166-173. doi:10.1086/518889

- Massoure PL, Reuter S, Lafitte S, et al. Pacemaker endocarditis: clinical features and management of 60 consecutive cases. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol. 2007;30(1):12-19. doi:10.1111/j.1540-8159.2007.00574.x

- Sohail MR, Uslan DZ, Khan AH, et al. Management and outcome of permanent pacemaker and implantable cardioverter-defibrillator infections. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2007;49(18):1851-1859. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2007.01.072

- Klug D, Lacroix D, Savoye C, et al. Systemic infection related to endocarditis on pacemaker leads: clinical presentation and management. Circulation. 1997;95(8):2098-2107. doi:10.1161/01.cir.95.8.2098

- Tarakji KG, Chan EJ, Cantillon DJ, et al. Cardiac implantable electronic device infections: presentation, management, and patient outcomes. Heart Rhythm. 2010;7(8):1043-1047. doi:10.1016/j.hrthm.2010.05.016

- Kusumoto FM, Schoenfeld MH, Wilkoff BL, et al. 2017 HRS expert consensus statement on cardiovascular implantable electronic device lead management and extraction. Heart Rhythm. 2017;14(12):e503-e551. doi:10.1016/j.hrthm.2017.09.001

- Gomes S, Cranney G, Bennett M, Giles R. Long-term outcomes following transvenous lead extraction. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol. 2016;39(4):345-351. doi:10.1111/pace.12812

- Lakshy G, Jayatilleke SK, Kottegoda SRP. Permanent pacemaker associated infective endocarditis caused by a member of the HACEK group of organisms: a case report. Sri Lankan J Infect Dis. 2018;8(1):40-45. doi:10.4038/sljid.v8i1.8143

- Patel SR, Patel NH, Borah A, Saltzman H. Aggregatibacter aphrophilus pacemaker endocarditis: a case report. BMC Res Notes. 2014;7:885. doi:10.1186/1756-0500-7-885