Peer Reviewed

Krabbe Disease

AUTHORS:

Samantha T. Kennedy, MD • Laura L. Hayes, MD • Johanna Kielbasa, MD

AFFILIATION:

Nemours Children’s Hospital, Orlando, Florida

CITATION:

Kennedy ST, Hayes LL, Kielbasa J. Krabbe disease. Consultant. 2021;61(8):e26-e30. doi:10.25270/con.2020.11.00008

Received June 28, 2020. Accepted October 26, 2020. Published online November 9, 2020.

DISCLOSURES:

The authors report no relevant financial relationships.

CORRESPONDENCE:

Samantha T. Kennedy, MD, Department of Pediatrics, Nemours Children’s Hospital, 6535 Nemours Pkwy, Orlando, FL 32827 (samantha.kennedy@nemours.org)

A 5-month-old full-term boy presented after having been transferred from a community hospital with decreased oral intake and poor urine output. On admission, he was hypertonic and irritable.

History. The boy’s parents reported worsening irritability since birth, poor weight gain since 2 months of age, and worsening oral aversion since 3 months of age. At 4 months of age, he had begun to exhibit hypertonia and developmental regression. He was essentially inconsolable unless held by his mother. His parents denied consanguinity.

Physical examination. The infant was thin, nondysmorphic, and inconsolable with mild hypertension (blood pressure, 97/82 mm Hg). His anterior fontanelle was large (4 × 3 cm) and sunken. He had an exaggerated-for-age head lag, poor eye contact and tracking, and weak suck. He was globally hypertonic with diffuse hyperreflexia.

Diagnostic tests. Laboratory evaluation revealed leukocytosis (white blood cell count, 18,000/µL; reference range, 8000-14,000/µL) and thrombocytosis (platelet count, 512 × 103/µL; reference range, 150-400 × 103/µL). The creatine kinase level was elevated (736 U/L; reference range, 24-170 U/L). Comprehensive metabolic panel results, C-reactive protein level, thyroid function test results, and lactate level were normal. Levels of ammonia and pyruvate were also normal. Quantitative serum plasma amino acid, quantitative serum acylcarnitine, and urine organic acid tests were performed, the results of which were unavailable at the time of diagnosis but ultimately were unremarkable. Urine and stool study findings were noncontributory. Chest and abdominal radiographs, head ultrasonograms, renal and abdominal ultrasonograms, and echocardiograms were all negative for abnormalities.

Due to his continued extreme irritability, a lumbar puncture and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) were pursued. Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) analysis revealed mildly elevated protein (238 mg/dL; reference range, <52 mg/dL), with negative cultures, meningoencephalitis panel, and autoimmune encephalitis panel.

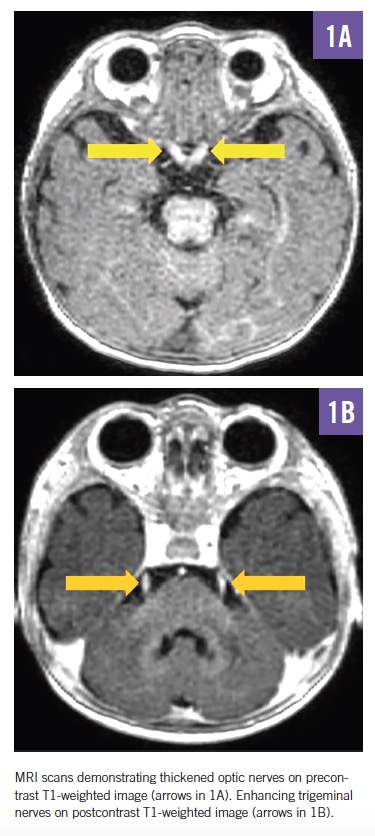

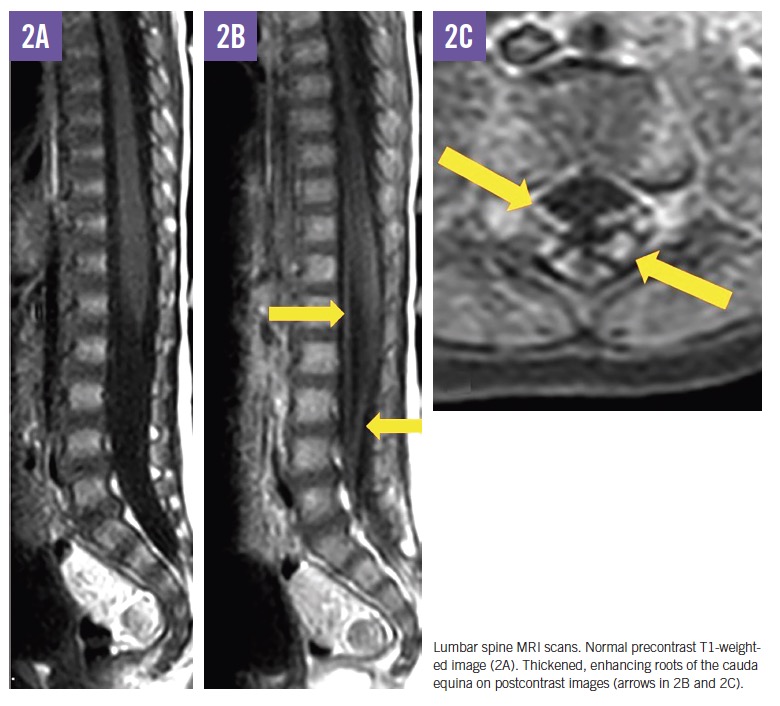

MRI scans of the brain and spine demonstrated increased T2 signal in the deep white matter, along the long spinal tracts, and involving the dentate nuclei. The optic nerves/optic chiasm and cauda equina were thickened and enhanced with contrast (Figures 1-3). MR spectroscopy demonstrated decreased N-acetyl aspartate (NAA) peak in the white matter with predominance of choline and myoinositol peaks (Figure 4). These results were in keeping with a diagnosis of Krabbe disease, which was later confirmed by targeted gene sequencing. The child was found to be homozygous for deletion of exons 11 through 17 in the galactosylceramidase gene (GALC), which is considered pathogenic.

Treatment and outcome. Intravenous normal saline and nasogastric tube feeds were initiated for failure to thrive with impaired oromotor function. He was discharged home with palliative care. His irritability was managed with morphine, up to 0.8 mg/kg/dose every 4 hours; gabapentin, 10 mg/kg/dose every 8 hours; lorazepam, 0.1 mg/kg/dose every 6 hours; and baclofen, 1 mg/kg/dose every 8 hours. The family has since relocated, and the patient has been lost to follow-up.

Discussion. Krabbe disease, also known as globoid cell leukodystrophy, is a lysosomal storage disorder with autosomal recessive inheritance. Danish neurologist Knud Krabbe, with collaborators Sven Monrad and Carl Edward Bloch, first associated 6 cases of acute infantile neurodegeneration between 1913 and 1916.1,2 These previously healthy infants had a sudden onset of extreme irritability; hypertonia with extensor spasms, nystagmus, and optic atrophy; developmental regression; weight loss; and intermittent hyperthermia between 4 and 5 months of age, with death occurring before 2 years of age. On autopsy, these children’s brains were found to be small and sclerosed.1,2

In Krabbe disease, a pathogenic variant in GALC leads to abnormal production of the enzyme galactosylceramidase (also known as galactocerebrosidase), which stimulates accumulation of toxic substrates.3,4 One of these toxic substrates is galactosylsphingosine (also known as psychosine), which is found in myelin-producing oligodendrocytes and Schwann cells.5 Psychosine accumulation induces neuronal cell death and myelin degradation.5,6 The other toxic substrate implicated in Krabbe disease is galactocerebroside, the major lipid component of the myelin sheath.7 Galactocerebroside accumulation recruits macrophages, which phagocytize debris and become the characteristic multinucleated globoid cells.5 The ultimate result of galactocerebroside and psychosine accumulation is undermyelination and malfunction of the central and peripheral nervous systems.

Krabbe disease usually presents in initially neurotypical children within the first 6 months with irritability, hypertonia, poor head control, poor feeding and failure to thrive, and motor and cognitive decline.8-10 Irritability often precedes other symptoms.10 Later-onset forms of Krabbe disease are associated with less irritability and seizures and more visual dysfunction.9,10

In symptomatic children, CSF protein levels are typically elevated.11 Neuroimaging most commonly reveals increased T2 signal in the periventricular and dentate nuclei, although a range of other changes may be seen, including enlargement of the optic nerve and optic chiasm and thickening of the cauda equina.12,13 Nerve conduction studies show progressively abnormal responses.11 Definitive diagnosis is made through enzyme and molecular genetic testing.

Differential diagnoses include infective and autoimmune encephalopathies, cerebral palsy, intracranial mass or bleed, traumatic brain injury, other leukodystrophies (eg, aspartoacylase deficiency), lysosomal storage disorders (eg, Sanfilippo syndrome, Niemann-Pick disease), glycogen storage disorders (eg, Gaucher disease), mitochondrial disease (eg, Alpers disease), and other genetic syndromes associated with neurologic dysfunction (eg, Rett syndrome).9

There is no cure for symptomatic Krabbe disease. Median survival is 2 years from age at diagnosis, although an estimated one-fifth of children survive until age 6 years.10 Treatment options are limited. Supportive care should address the child’s symptoms, including antispasmodic and antiseizure medications; chest physiotherapy for poor secretion control; and nutritional support with tube feeding and reflux or constipation interventions as needed.11 There is scant evidence to guide treatment of irritability. The authors of a case study of 2 infants noted improvement with oral morphine, up to 0.1 mg/kg every 8 hours.14 Parents should be connected with local and national support resources. End-of-life care goals should be ascertained. Future pregnancies should be planned with a genetic counselor.

Hematopoietic stem-cell transplant demonstrates decreased morbidity and mortality in asymptomatic children only, if initiated before 30 days of life.15 Therefore, 7 states (Illinois, Kentucky, Missouri, New York, Ohio, Pennsylvania, and Tennessee) screen newborns for GALC deficiency with dried blood spots. Referral to transplant should be made judiciously, because the procedure carries significant morbidity and mortality, all children undergoing transplant have had varying amounts of persistent motor and/or cognitive disability, and no benefit has been shown to children older than 1 month.11

Emerging research suggests the future feasibility of gene therapy to replace pathogenic GALC variants with a functional gene; enzyme replacement therapy with galactocerebrosidase harvested from healthy cells; molecular chaperone therapy to improve galactocerebrosidase folding and function; psychosine inhibitors; and anti-inflammatory compounds to attenuate the neuroinflammatory response.16

REFERENCES:

- Krabbe K. A new familial, infantile form of diffuse brain-sclerosis. Brain. 1916;39(1-2):74-114. doi:10.1093/brain/39.1-2.74

- Compston A. A new familial infantile form of diffuse brain-sclerosis. Brain. 2013;136(pt 9):2649-2651. doi:10.1093/brain/awt232

- Suzuki K, Suzuki Y. Globoid cell leucodystrophy (Krabbe’s disease): deficiency of galactocerebroside β-galactosidase. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1970;66(2):302-309. doi:10.1073/pnas.66.2.302

- Suzuki K. Globoid cell leukodystrophy (Krabbe’s disease): update. J Child Neurol. 2003;18(9):595-603. doi:10.1177/08830738030180090201

- Graziano ACE, Cardile V. History, genetic, and recent advances on Krabbe disease. Gene. 2015;555(1):2-13. doi:10.1016/j.gene.2014.09.046

- Miyatake T, Suzuki K. Globoid cell leukodystrophy: additional deficiency of psychosine galactosidase. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1972;48(3):539-543. doi:10.1016/0006-291x(72)90381-6

- Morell P, Quarles RH. Myelin formation, structure and biochemistry. In: Siegel GJ, Agranoff BW, Albers RW, Fisher SK, Uhler MD, eds. Basic Neurochemistry: Molecular, Cellular and Medical Aspects. 6th ed. Lippincott-Raven; 1999:chap 4.

- Duffner PK, Jalal K, Carter RL. The Hunter’s Hope Krabbe family database. Pediatr Neurol. 2009;40(1):13-18. doi:10.1016/j.pediatrneurol.2008.08.011

- Liao P, Gelinas J, Sirrs S. Phenotypic variability of Krabbe disease across the lifespan. Can J Neurol Sci. 2014;41(1):5-12. doi:10.1017/s0317167100016188

- Beltran-Quintero ML, Bascou NA, Poe MD, et al. Early progression of Krabbe disease in patients with symptom onset between 0 and 5 months. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2019;14(1):46. doi:10.1186/s13023-019-1018-4

- Escolar ML, West T, Dallavecchia A, Poe MD, LaPoint K. Clinical management of Krabbe disease. J Neurosci Res. 2016;94(11):1118-1125. doi:10.1002/jnr.23891

- Abdelhalim AN, Alberico RA, Barczykowski AL, Duffner PK. Patterns of magnetic resonance imaging abnormalities in symptomatic patients with Krabbe disease correspond to phenotype. Pediatr Neurol. 2014;50(2):127-134. doi:10.1016/j.pediatrneurol.2013.10.001

- Hwang M, Zuccoli G, Panigrahy A, Rodriguez D, Poe MD, Escolar ML. Thickening of the cauda equina roots: a common finding in Krabbe disease. Eur Radiol. 2016;26(10):3377-3382. doi:10.1007/s00330-016-4233-6

- Stewart WA, Gordon KE, Camfield PR, Wood EP, Dooley JM. Irritability in Krabbe’s disease: dramatic response to low-dose morphine. Pediatr Neurol. 2001;25(4):344-345. doi:10.1016/s0887-8994(01)00326-5

- Kwon JM, Matern D, Kurtzberg J, et al. Consensus guidelines for newborn screening, diagnosis and treatment of infantile Krabbe disease. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2018;13(1):30. doi:10.1186/s13023-018-0766-x

- Won JS, Singh AK, Singh I. Biochemical, cell biological, pathological, and therapeutic aspects of Krabbe’s disease. J Neurosci Res. 2016;94(11):990-1006. doi:10.1002/jnr.23873